|

By Allison Wharton, Byrd Center Student Intern On February 12, 1999, the United States Senate voted to acquit President Bill Clinton of his impeachment charges, finding him not guilty of obstruction of justice or perjury.[1] Clinton’s acquittal was the end result Senator Robert C. Byrd along with many other Senators had hoped for, believing it to be the best decision for the country by the end of the trial.

Initial investigation of President Clinton began in January, 1994, when lawyer Robert B. Fiske Jr. was appointed to independent counsel by attorney general Janet Reno. Fiske was tasked with examining criminal financial allegations of the Whitewater scandal first brought up in 1992 during Clinton’s campaign and election over real estate purchased by the president.[2] Only days before the investigation was opened, however, Clinton was already facing the beginning of separate criminal allegations after Paula Jones, his former employee while serving as Senator of Arkansas, came forward to file a civil suit against the sitting president for sexual harassment. [3] By the end of 1994, a United States Court of Appeals elected to remove Fiske from his position, replacing him with former federal judge Kenneth Starr, who had worked under the Reagan and Bush Administrations.[4] Senator Robert C. Byrd, as a major figure in the Democratic Party, expressed significant concerns with the route of the investigation and its impact on Congress. Though expressing that the Whitewater controversy was being handled correctly by going through Congress for approvals, on December 20, 1995, Byrd expressed concerns over partisan dispute before a Senate vote on enforcing the subpoena of documents connected to Whitewater.[5] Byrd pointed out the major and increasing divide in party opinions. As harsh criticisms of the president and other politicians plagued Congress, Byrd emphasized the need for “civility” in the Senate, stating, “Political partisanship is expected in a legislative body, we all engage in it. But bitter personal attacks go beyond the pale of respectable propriety.” Nonetheless, Kenneth Starr’s vigorous investigation of the president continued. In November of 1996, President Clinton was reelected to office despite the accusations of his first term, defeating Senator Bob Dole (R-KY) after receiving 49 percent of the country’s vote.[6] Throughout 1997, as party lines remained divided, Starr drafted impeachment referrals based on subpoenaed documents from 1995-96, yet did not find substantial evidence to make a case against Clinton.[7] By the end of 1997 though, Starr finally received the information he had been looking for nestled within accusations against Clinton in the Paula Jones case after Jones’ lawyers received a private tip from White House staffer Linda Tripp. Ms. Tripp stated that while working, she had become friends with White House intern Monica Lewinsky, who had, according to Tripp, bragged to her frequently about having an affair with Clinton.[8] Lewinsky’s story, if confirmed, could show patterns of sexual behavior toward women employees by Clinton. At the beginning of 1999, Tripp discovered that Lewinsky had signed an affidavit claiming that she had not had an intimate relationship with Clinton. In response, Tripp handed over hours of her conversations with Lewinsky that she had recorded that could be beneficial to Starr’s investigation of the president. [9] With news of Clinton’s affair reaching the public as media outlets began receiving information on the scandal and party hostility picking up again as Starr moved forward, President Clinton addressed addressed the nations growing concerns, claiming infamously on January 26, “did not have sexual relations with that woman, Miss Lewinsky.” As talk of impeachment arose with Clinton confessing his affair to the nation in August of 1999, the media and fellow congressmen alike turned to Senator Robert C. Byrd for answers about the constitutional processes of impeachment.[10] Byrd was said to be “a believer in holy documents,” citing both the bible and U.S. constitution as they “the sacred tools for defending his Senate against the savages,” and was respected by both parties for his commitment to the constitution and tradition.[11] However, it was Starr’s document of his findings during his investigation that was at the forefront of their focus after its release on September 9, 1999. On the morning of September 11, 1999, President Clinton spoke of his morality at a prayer breakfast, citing his hopes to repent and calling himself a “broken spirit.”[12] However, despite Clinton’s sentimental speech, Americans were captivated instead by the release of The Starr Report to the public on the internet the same day. With the entire nation now having access to such explicit material and a further spark of media frenzy, members of Congress began to question the appropriateness of the report, despite Starr’s finding of 11 potential impeachable offenses. Some congressmen deemed it to be too “offensive and graphic,” with The Washington Post quoting Philadelphian lawyer Lawrence Fox who analogized the situation by explaining that “you don’t have to show the severed head of a victim to show that a victim died.”[13] Senator Byrd, however, had already spoken to the Senate in a speech entitled “No Rush to Judgment,” expressing his concerns and noting the blunders of the president before the release of “The Starr Report.” Byrd compared the Clinton Scandal to Watergate, stating that while during Nixon’s case he believed that “hard evidence” mattered most, public opinion would have a much bigger role in Clinton’s impeachment, should it move forward. As the so-called “guardian” of the senate, expert on the constitution, and a Senator well-respected by both parties, Byrd reviewed his personal reading of the complexities of impeachment and the seemingly “sparse” nature of the phrase “crimes and misdemeanors.” Above all, he urged the Senate should remain calm and refrain from making any rash judgments, as the Senate’s role in impeachment would begin only after going through the House. Despite such a divide in party lines, the House Judiciary elected to finally begin their formal inquiry in October, 1998.[14] Of the eleven counts of impeachable offenses suggested by Kenneth Starr in his report on Clinton, House Judiciary members found two counts of perjury, obstruction of justice, and abuse of power as valid charges against the president.[15] The Judiciary Committee wrote and prepared a series of questions for the president based on the findings of independent council Starr, but the time of the House’s questioning of Clinton and drafting of impeachment articles, the president had already been dealing with one less issue after the case of Paula Jones sexual harassment case was dismissed. While dismissed due to lack of evidence, in November, as the House moved forward, Clinton paid Jones 850,000 dollars without giving any further public commentary.[16] Across the country, aggressive public debate over Clinton’s morality and leadership continued as Americans tried to make sense of his relationships with both Jones and Lewinsky and the suggested charges of impeachment against him. Though Democratic Party members had major worries from the start of accusations against Clinton, they gained seats in the House during the midterm election of November of 1998 with indication that much of the public was against beginning impeachment proceedings.[17] Independent counsel Kenneth Starr spoke to the House about his investigation of the president, explaining that he had spent 1997 drafting impeachment recommendations but had found no supporting evidence.[18] Despite clearing the president of accusations of the Whitewater scandal, there were now sound arguments in favor of impeachment and more reason to move forward. Thus, on December 11, the House Judiciary moved to recommend the impeachment of President Clinton, on four articles of “high crimes and misdemeanors” to the House.[19] After years of Starr’s multi-million dollar investigation, months of review by Congress, and public and media captivation, on December 19, 1998, the House of Representatives voted to impeach President Bill Clinton on charges of perjury and obstruction of justice for lying under oath and the attempted cover-up of his affair.[20] Sources: [1] “How the Senate Voted on Impeachment,” CNN, Feb. 12, 1999, https://www.cnn.com/ALLPOLITICS/stories/1999/02/12/senate.vote/. [2]“Timeline: Whitewater Political Report.” The Washington Post, 1998, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/special/whitewater/timeline.htm. [3] “Bill Clinton-Key Events.” Miller Center of Public Affairs. University of Virginia, Accessed July 6, 2020, https://millercenter.org/president/bill-clinton/key-events. [4] Olivia B. Waxman and Merrill Fabry, “From Anonymous Tip to an Impeachment: A Timeline of Key Moments in the Clinton-Lewinsky Scandal,” Time, May 4, 2018, https://time.com/5120561/bill-clinton-monica-lewinsky-timeline/. [5] “Timeline: Whitewater Political Report.” [6] “Bill Clinton-Key Events.” [7] “Timeline: Whitewater Political Report” [8] Olivia B. Waxman and Merrill Fabry, “From Anonymous Tip to an Impeachment: A Timeline of Key Moments in the Clinton-Lewinsky Scandal.” [9] Ibid. [10] Neil A. Lewis, “Impeachment Puts Spotlight on ‘Guardian’ of the Senate,” New York Times, Dec. 27, 1998. [11] Ahrens, Frank. “Robert Byrd’s Rules of Order.” The Washington Post, Feb. 11, 1999. [12] Bill Clinton, “I Will Continue on the Path to Repentance,” In The Starr Report, Kenneth Starr (New York: PublicAffairs, 1998), xxv-xxvii. [13] Michael Grunwald, “Report’s Details on Sexual Acts Prompts Regret,” In The Starr Report, Kenneth Starr (New York: PublicAffairs, 1998), xxviii-xxx. [14] Olivia B. Waxman and Merrill Fabry, “From Anonymous Tip to an Impeachment: A Timeline of Key Moments in the Clinton-Lewinsky Scandal.” [15] Ibid. [16] “Bill Clinton-Key Events.” Miller Center of Public Affairs. University of Virginia. [17] Ibid. [18]“Timeline: Whitewater Political Report.” The Washington Post, 1998. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/special/whitewater/timeline.htm. [19] Sarah Wire. “A Look Back at How Clinton’s Impeachment Trial Unfolded.” LA Times, Jan. 16, 2020.https://www.latimes.com/politics/story/2020-01-16/a-look-back-at-how-clintons-i Mpeachment-trial-unfolded. [20] John King, “House Impeaches Clinton,” CNN, Dec. 19, 1999, https://www.cnn.com/ALLPOLITICS/stories/1998/12/19/impeachment.01/

2 Comments

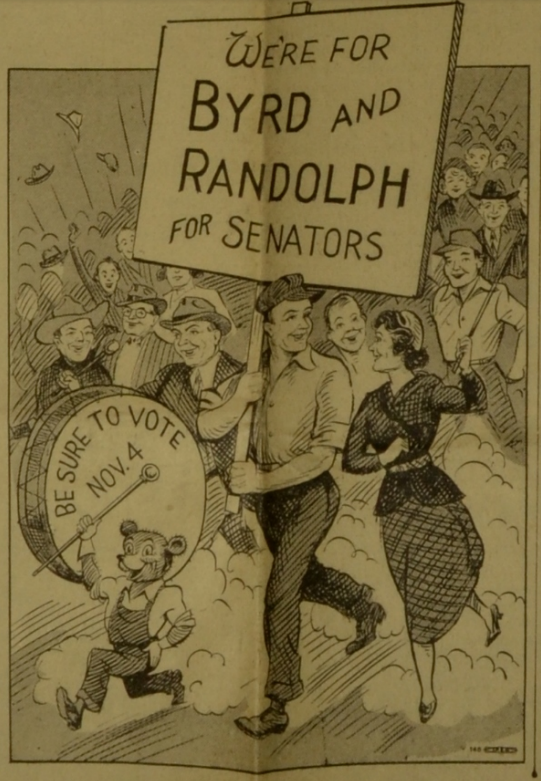

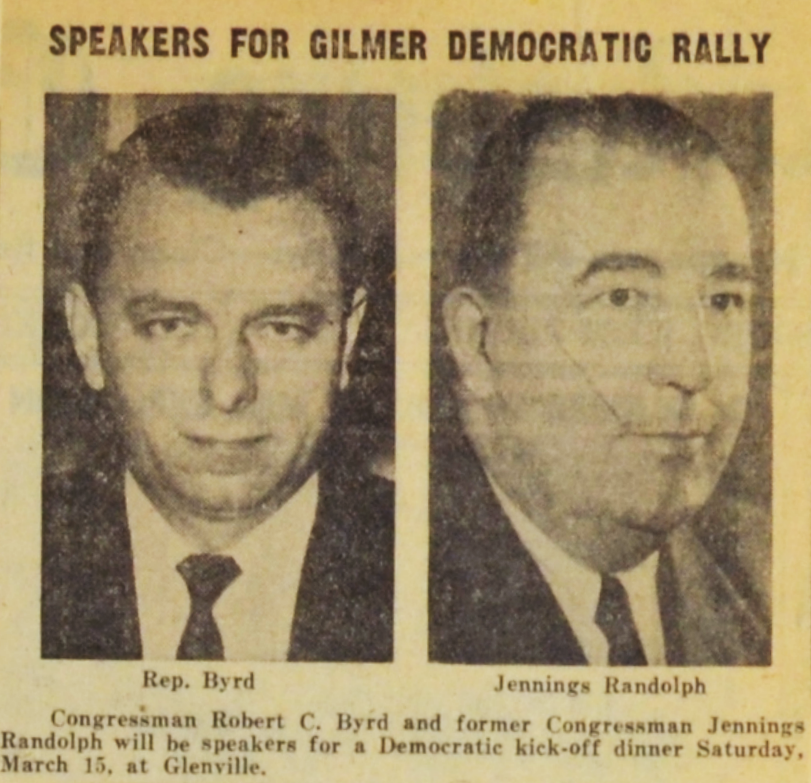

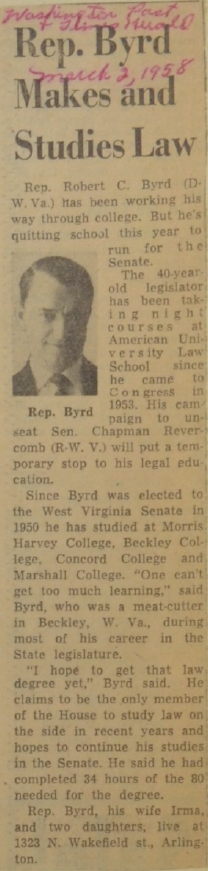

By Victoria Myers, Byrd Center Student Intern The election of 1958 was only the third time in a century that both of West Virginia's Senate seats were open. Two years earlier, Senator Harley M. Kilgore died in office. A special election was held in which Republican Senator Chapman Revercomb was elected to serve the remaining two years of Senator Kilgore's term. In early-1958, the death of Senator Matthew Mansfield Neely, a veteran of the Spanish American War who spent thirty-three years in Congress, left a vacancy with two years remaining in his unexpired term. Charleston lawyer John D. Hoblitzell, Jr., was appointed to fill Senator Neely's seat until that fall's election. By mid-1958, two prominent Democratic candidates announced their intentions to run for the seats: former West Virginia Representative Jennings Randolph, and then-serving Congressman Robert C. Byrd. In an oral history with Senate Historian Richard Baker, Senator Byrd talked about this unusual circumstance: “We [Byrd and Randolph] teamed up since we were not running against each other, and we were running for two separate seats. We ran as a team. In those days campaigning consisted mainly of traveling around the state, speaking in courthouses--at courthouse rallies, speaking in union halls and before rallies of coal miners, and speaking at the chamber of commerce meetings and meetings of civic organizations, and going to things of that nature.”

West Virginia in the United States Senate''. Byrd having established his name in southern West Virginia and Randolph being well-known across the state, Byrd’s campaign strategies focused particular attention on the state's southwestern counties where the economic and social issues aligned closely with those counties he had already represented in the House of Representatives for the past six years. Early in the campaign while traveling between public appearances on March 17, 1958, Jennings Randolph was driving on State Route 2 near New Martinsville when he fell asleep at the wheel and veered into oncoming traffic, killing Ricardo Cortez. Randolph suffered a broken rib, bruises, and cuts while Byrd, who was a passenger in the car, only received a cut lip. After an investigation, no charges were filed against Randolph and Byrd's insurance provided payment to Cortez's family. The incident was reported across the state, leading one of Randolph and Byrd's opponents to declare "West Virginia doesn't want a sleeping senator." Despite the tragedy, the campaign continued on. As the pair started their campaign for the August primary for the democratic election, Senator Byrd decided to take time away from his studies at the American University Washington College of Law to pursue the race. After Bryd applied for the senate seat, Charles C. Morris announced that he would run for Byrd’s current seat as the democratic candidate for Congress. The kick-off to their campaign started at Hotel Conrad in Glenville for the “Democrats for Victory'' dinner on March 15, 1958, where Randolph and Byrd spoke together. The dinner served as a formal political launch for the Senate race and showcased what the former Congressmen Randolph and current 6th district Representative Byrd wanted to bring to the position. Byrd spoke sternly about bringing an end to the present economic recession which caused a lower standard of living, rising unemployment, and greater inflation across Appalachia. He declared that night: “We must have forthright enlightened and strong leadership in the United States; determination at all levels and in all branches of government to work for an end to this recession and cut away the diseased roots of the domestic economy and government policy which caused it- and with the least possible delay”. He then listed nine actions the United States should take to combat this recession. Randolph introduced seven major policies to improve domestic and foreign affairs, insisting that “the time is now to do things, not wait.” Billboards, interviews, along with advertisements in newspapers, radio, and even a few broadcast on television, were key ways that Byrd and Randolph shared their visions. The campaign was ran on a combined fund of $50,000 with one of their key endorsements coming from Lois Lilly Kilgore, the wife of the late Senator Kilgore.

On August 5, 1958, West Virginian's went to the primary polls to choose their party nominations. The candidates for the two-year term left by Senator Neely were Jennings Randolph, West Virginia Governor William C. Marland, Attorney Arnold M. Vickers and W.R. Wilson. In addition to Robert C. Byrd, Charleston Attorney Fleming N. Alderson and Jack R. Delligatti of Fairmont vied for the full senate term. Randolph and Byrd emerged victorious from the primary and began their campaign against their respective Republican opponents: John D Hoblitzell, Jr., and Chapman Revercomb.

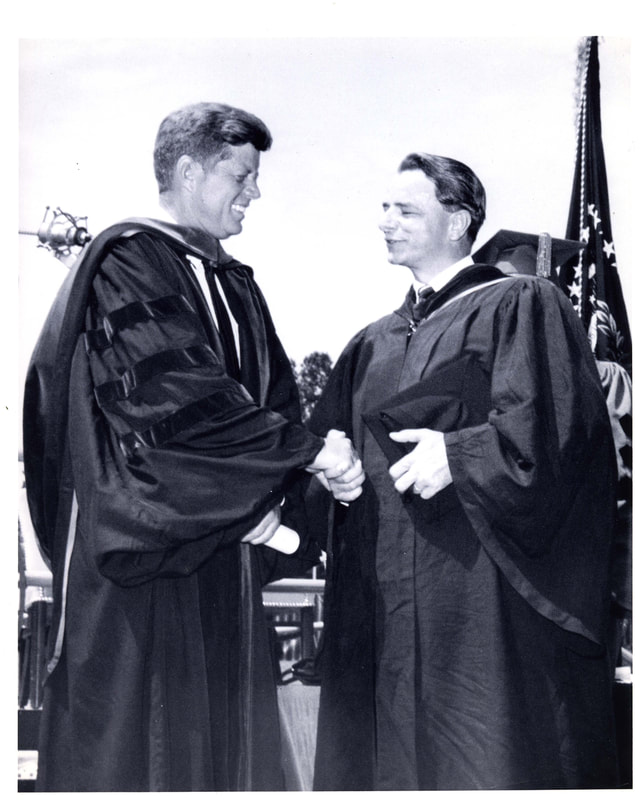

A month before election day, Byrd urged "all voters to be sure they are properly registered for the general election" in a newspaper advertisement. Polls and surveys across the state projected a victory for Byrd and Randolph. On November 4, 1958, the voters cast their ballots, with Byrd receiving 118,573 votes or 58.26 % of the total electorate over Revercomb. Randoph received 117,657 or 59.32% in his race against Hoblitzell, Jr. The next day, newspaper headlines declared “Byrd and Randolph Elected to the Senate in a Landslide Victory”. On January 3, 1959, Senators Jennings Randolph and Robert C. Byrd were sworn into the U.S. Senate by Vice President Richard M. Nixon. The unusual circumstances of the 1958 election in West Virginia cemented the campaigns of Senators Randolph and Byrd in the history books. By Victoria Myers, Byrd Center Student Intern Senator Robert C. Byrd’s childhood shaped several strong beliefs that guided his life and political career. In an oral history interview conducted by Frank Van Der Linden, Senator Byrd reminisced on the beginning of his political journey. Speaking about the need to address coal miner’s issues for any campaign taking place in West Virginia, Senator Byrd remarked “I don’t mean to say I had only their interests at heart, for I tried to serve the school teachers, the veterans, and all the people.” From the beginning of his career, Senator Byrd believed in enhancing education in our state. Raised by a coal miner father who encouraged him to devote his attention to his education by buying him books and watercolors instead of toys, Senator Byrd excelled in school. This drive for improving himself through education overcame obstacles from walking three miles to the school bus every morning and evening, to balancing his pursuit of a law degree while serving in the United States Congress.

Education is not always about individual learning; it is also about teaching and communicating with others. As a young adult, Byrd taught a Sunday School class for boys at his church in Sophia, West Virginia. In addition to their religious instruction, Senator Byrd engaged his students in athletic activities and taking them on field trips to the State Capitol in Charleston as well as Washington, D.C., where the small-town boys saw and experienced the excitement and opportunity of these cities. His efforts through this Sunday School class inspired his students own lifelong passions for knowledge and new experiences. Senator Byrd stated in the interview with Frank Van Der Linden, “In this country, we need mathematicians, we need scientists, we need historians, we need music teachers, we need to develop not only the body but also the soul, the heart, and the mind.” Through his own experience it is easy to see that he put great value on education and wanted the people of West Virginia to gain more knowledge for their futures and that of their state. Throughout his political career, Senator Byrd was an outspoken supporter of increasing teachers' salaries. He purchased saving bonds to give as scholarships to every valedictorian in West Virginia’s high schools. In 1991, Senator Byrd wrote a Byrd’s-Eye View column talking about his national scholarship program, stating: “these scholarships are intended to encourage excellence in education by giving motivated students assistance in pursuing their college educations."

Wanting to inspire students to have a greater understanding of the foundation of the United States government, Senator Byrd added an amendment to the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2005 to establish Constitution Day. In his Byrd's-Eye View column, Senator Byrd explained "Our citizens must be familiar with the Constitution and the intent of the Framers who wrote it. I included a provision in U.S. law which designates September 17 of each year as Constitution Day, so that, on or near this day, all Americans can learn more about the Constitution and reflect upon its importance. Once again this year, September 20, 2006 schools in West Virginia and throughout our country offered special Constitution Day programs.” Senator Byrd's own desire to learn placed education at the forefront of his efforts to support the people in West Virginia. His journey was one of the hardships and lessons that helped shape his approach to providing educational opportunities for more students in his state and across the nation. Senator Byrd's 1977 oral history interviews with Frank Van Der Linden can be read in full here >> By Allison Wharton, Byrd Center Student Intern The censorship of the internet, particularly on social media, has been a topic of scrutiny and political debate this year. While social media allows for easier spread of ideas and can be used by businesses and professionals for marketing, it is widely regarded as a form of entertainment rather than a medium with any major educational value.[1] The popularity of social media in the 21st century has surpassed traditional forms of media entertainment such as television, but the debate over censorship and the purpose of social media is a continuation of long-standing discussions over the constitutionality of entertainment regulation, which has been addressed by all three branches of government over the past fifty years.[2] From the 1970s until his death, Senator Robert C. Byrd wrote and spoke frequently in favor of censorship of entertainment media, notably commenting on television, music, and the correlations between culture and crime rates. Byrd’s primary concern with the entertainment industry was the effect it had on children, citing television as a major factor in the decline of his perception of societal morality. In an edition of Byrd’s weekly news column, Byrd’s Eye View, entitled “Television: A New Medium for Child Abuse?” he wrote:

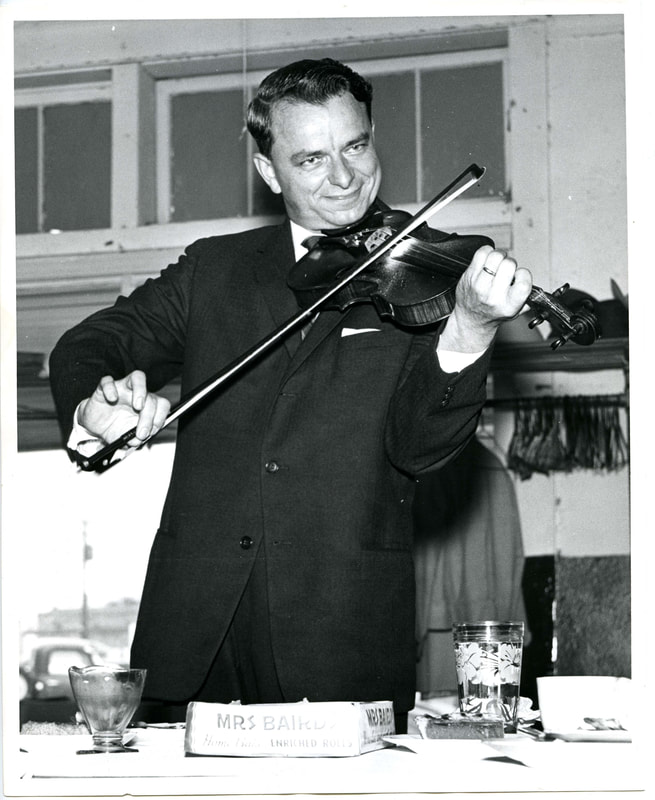

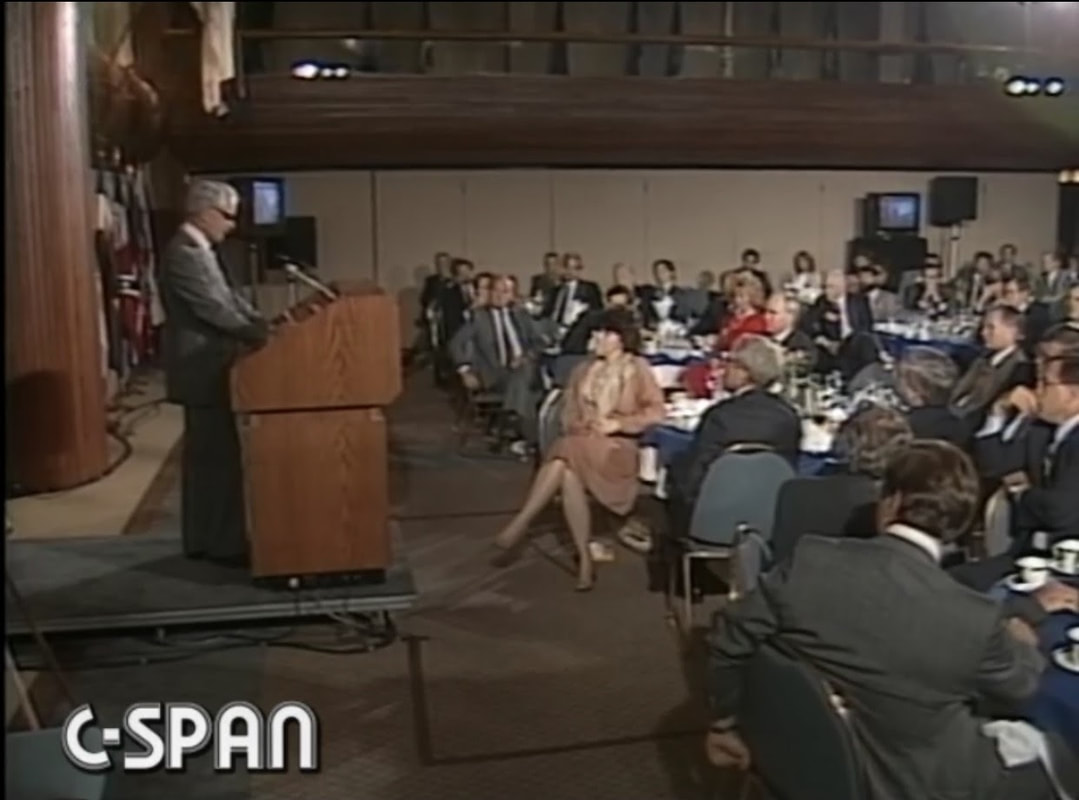

Though Senator Byrd was quite vocal about his problems with entertainment media, he also recognized the potential benefits. He believed that television and music would be better used for educational purposes than entertainment. Byrd grew up learning how to play the fiddle, recording an album and frequently playing at public appearances throughout his adult life. While arguing for regulation of the music industry, Byrd did recognize its merit. He also appeared on the show “Hee Haw,” despite his seemingly outspoken opposition to television and argued that a “Family Hour” program was necessary for the entertainment industry because it would provide appropriate forms of entertainment that could also be educational. Senator Byrd was initially lukewarm to the idea of televising floor proceedings of the U.S. Senate when C-SPAN was created in 1979. However, he came to realize the democratizing value that television coverage of the Congress could build and he ultimately became an ardent supporter of allowing cameras into the Senate Chamber in 1986. Byrd’s belief in the regulation of entertainment media was due to his hope for the youth of the country to be better educated rather than to be exposed to themes he cited as the cause for increase in juvenile crime. According to the Federal Communications Commission, material considered “indecent” is protected under the First Amendment and cannot be completely censored.[3] Various members of Congress have spoken both for and against censorship of entertainment and the Supreme Court has a long history of cases on obscenity charges and freedom of speech.[4] Byrd’s reputation as a strict constitutionalist despite rulings to protect entertainment media from censorship reflects the complexity of regulation of the entertainment industry that is still happening today. Social media serves as a form of short-term entertainment, while the shift toward more fact-based and educational usage has the potential to have a larger impact.[5] However, lack of censorship makes the validity of claims more difficult to confirm and potentially allows for the posting of more obscenities, while over-censorship or censorship of free speech would be deemed unconstitutional. The same arguments on social media regulation existed long before in discussion of the censoring of television and music. The debate on social media censorship, fact checking, and algorithmic issues are an extension of larger debates about entertainment that stretch back to the mid-20th century and continue into modernity. Sources:

[1] Stuart Cunningham and David Craig, Social Media Entertainment: The New Intersection of Hollywood and Silicon Valley, (New York: NYU Press, 2019), 8-11. [2] “A Brief History of Film Censorship,” National Coalition Against Censorship, Accessed June 20, 2020, https://ncac.org/resource/a-brief-history-of-film-censorship. [3] “Consumer Guides: Broadcast, Cable, and Satellite,” Federal Communications Commission, Last modified May 18, 2020, https://www.fcc.gov/general/broadcast-cable-and-satellite-guides. [4] “Freedom of Expression in the Arts and Entertainment,” American Civil Liberties Union, February 27, 2002, https://www.aclu.org/other/freedom-expression-arts-and-entertainment. [5] Brian Patrick Green, “What is the Main Purpose of Social Media: Entertainment or Education?” Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University (blog), December 16, 2019, https://www.scu.edu/ethics-spotlight/social-media-and-democracy/what-is-the-main-purpose-of-social-media-entertainment-or-education/ By Erik Minyard, Byrd Center Student Intern The United States has engaged in two wars with Iraq, the latter ongoing conflict becoming the longest war in American military history. The first conflict with Iraq, the Persian Gulf War, was widely opposed by the American public, who felt that while Iraq's invasion of Kuwait was wrong, it was not cause for the United States to involve itself with the conflict between the two Middle Eastern nations. The second conflict was less opposed by an American public reeling from the tragedy and paranoia of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. However, Senator Robert C. Byrd and 22 of his colleagues in the Senate felt that the Iraq War of 2002 was unjust and would forever change the way the United States handles foreign policy and the decision of going to war. The United States first war with Iraq took place in the early- 1990s after the Iraqis invaded Kuwait, violating rules that were placed by the United Nations. Iraq invaded Kuwait after accusing them of drilling into Iraqi oil fields in Rumaila. Demanding $100 billion from the Kuwaiti government, Iraq threatened an invasion over the oil dispute. Global concern arose with Iraq’s severe response to Kuwait because they violated many of the terms that were placed by the United Nations and they showed no signs of heeding any warnings to halt their offensive tactics. Of growing concern was Iraq’s stated interest in the development of weapons of mass destruction which included chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons. The Persian Gulf War lasted five months with much of the United States Armed Forces involvement taking place during Operation Desert Storm in early-1991. While many Americans generally opposed our involvement in the Persian Gulf War, opinions surrounding our second and ongoing conflict with Iraq were more mixed. After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the United States Congress passed an authorization of the use of force against any nations, organizations, or people harboring or supporting terrorist organizations. The first war entered under this arrangement was in Afghanistan where the government was harboring Al Qaeda, the organization which planned, executed, and claimed credit for the attacks. This caused America to send troops to many countries and would make it harder for political relations and diplomacy to take place in the Middle East. The renewed military focus in the Middle East also led some Americans to feel that the government was overstepping its power. In late-2002, the Bush Administration pushed for an authorization of use of force against Iraq on allegations of aid to terrorists and the threat of weapons of mass destruction. The second war with Iraq was seen as a dangerous precedent by 23 members of the Senate who believed that the executive branch was making a massive overreach of power and that an unprovoked attack on Iraq would only make matters worse. While some Americans shared this point of view, many others supported the war out of fear that something needed to done to prevent another terrorist attack like that of September 11, 2001. Senator Byrd chastised his fellow members in a floor speech in February 2003 because there was little debate or serious oversight of the war in Iraq. Senator Robert C. Byrd felt that going to war with Iraq was unjust because there was no cause for the war apart from the U.S. claiming that they could be a problem in the future. The war in Iraq also represented a dangerous precedent of the United States entering a conflict without any provocation and acting unilaterally without the support and against the advice of our global allies. Byrd felt that the best course of action was to stay out of a war with Iraq and to make deals with them to prevent the development or use of weapons of mass destruction. Reflecting on his vote nearly forty years prior supporting the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War, Senator Byrd felt that he had made the wrong choice then and now he wanted to make the right choice and try to stop the U.S. from entering another conflict that would only cause more trouble than good.

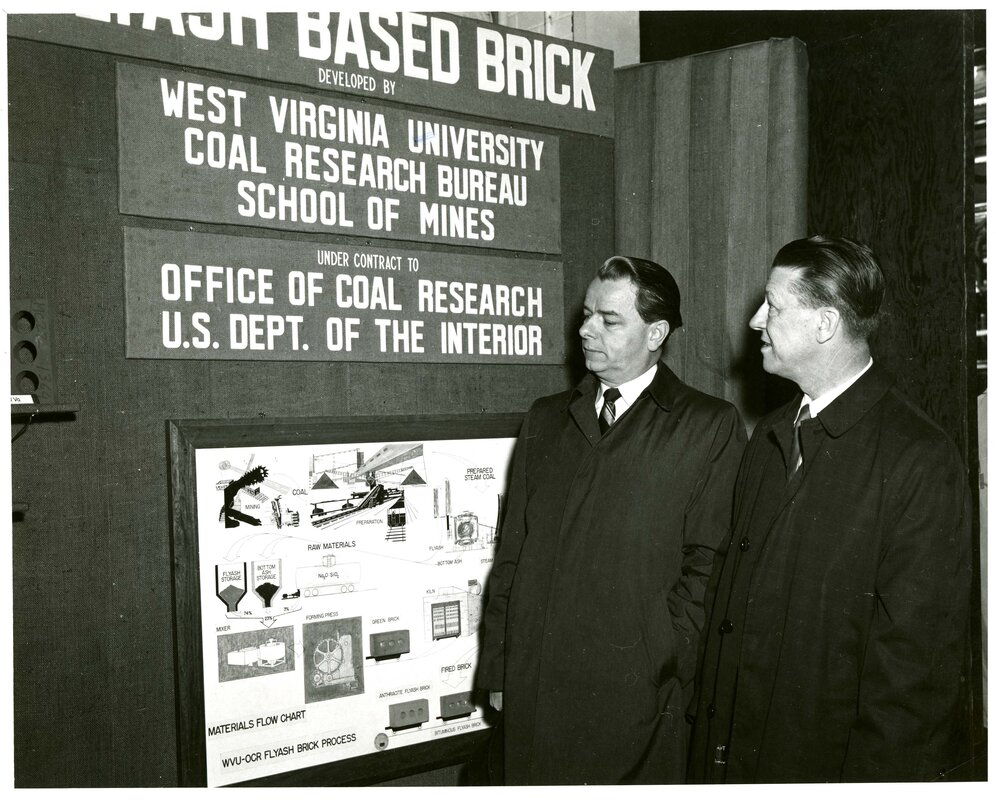

Despite Senator Byrd’s speeches and the twenty-two other Senators who voted with him, the United States determined to reenter a state of war with Iraq, staging the first invasion in early-2003. The Iraq War has become America's longest-lasting conflict and many on the national and global stages view the actions taken in Iraq as being short-sighted in the larger diplomatic situation in the Middle East that continues to stir conflict today. Since the passage of authorizations of the use of force in the Middle East following September 11, 2001, the United States has been embroiled in conflicts with Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Iran, and the Islamic State. Sources: “War in Iraq Begins.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, November 24, 2009. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/war-in-iraq-begins. “FRONTLINE/WORLD . Iraq - Saddam's Road to Hell - A Journey into the Killing Fields . PBS.” PBS. Public Broadcasting Service. Accessed July 28, 2020. https://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/iraq501/events_kuwait.html. By Erik Minyard, Byrd Center Student Intern In 1970, an energy crisis hit America; this was no surprise to Senator Robert C. Byrd who foresaw and made several attempts to prevent the crisis. Byrd made several attempts to warn of the problems that we could face supplying most of our energy needs on foreign oil, but oil was abundant for import and it could be used to power almost anything the American people needed. The crisis hit as developing tensions in the Middle East and U.S.- Arab relations led to the embargo of oil trade with the United States. Senator Byrd went on a tour of Europe and the Middle East in the 1950s. While he was visiting the Arab States, he noticed that many of them were making arms deals with the Soviet Union for weapons. When Senator Byrd asked about the arms deals with the Russians, Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser claimed that it was for their own protection. “Colonel Nasser in Egypt insisted that arms from the Soviets did not mean that his country would become subservient to the Russians, but Egyptians desire for arms was motivated by the desire for protection against Israel.” This was one of the many rising tensions in the Middle East, problems which stemmed from the creation of the Israeli state and rise in wealth from oil extraction and trading. Many of the Arab States felt that their land and holy sites had been unjustly taken from them which fueled openly hostile relations towards Israel and any country that supported them. Due to rising tensions, Senator Byrd urged the U.S. Senate to place a tariff on the import of oil and to switch its main source of power from oil to coal. Senator Byrd felt that if the U.S. kept relying heavily on oil that it would cause an energy crisis as political problems continued to mount in the Middle East. The United States was one of the supporters for the creation and protection of Israel. In an attempt to sway countries from supporting Israel, Arab nations unified in the creation of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) with the goal of leveraging greater power in trade negotiations. Continued American support for Israel after the Six Day and Yom Kippur Wars led OPEC to call for an embargo on oil exported to the United States in 1973. Just as Senator Byrd had predicted, the embargo led to a spike in prices and shortages of oil across the United States. In the years leading up to the energy crisis, Senator Byrd worked to diversify the uses of coal in an attempt to strengthen its domestic market opportunities and to support the ailing industry which had long been the economic mainstay of West Virginia. He worked through the Senate Appropriations Committees to secure funding for the establishment of “Project Bootstrap” to study and create new sources of power that would replace oil. If technology could develop more efficient uses of coal for energy, the market could be further expanded by other uses of the material which was still considered to be abundant in West Virginia and other coalfields across the country. The idea of turning coal into gasoline was a key objective of Project Bootstrap and a test plant was created in Morgantown, West Virginia to develop this concept. Project Bootstrap funded research into new and innovative uses for coal, including its use as an insulation material, brick production, and as an agent to increase decomposition in landfills. Though Senator Byrd's attempts to regain coal’s preeminent place in the U.S. energy market failed, he did not stop trying to persuade the public that our dependence on foreign imported oil was potentially dangerous to our economy. In a Byrd’s-Eye View column in 1970, Byrd wrote that “The energy shortage in America can only get worse if action is not taken immediately to insure an always sufficient supply of fuel to run power plants.” The shortage of oil caused problems for all people and could lead to unrest among the public if it were to continue. Senator Byrd also attested to his belief that coal was still a viable source for power, stating “it is of the utmost importance that the government undertake intensified research on natural fuels for energy production.” An increased use of coal would not only provide much-needed economic relief and jobs to his home state, but it would better prepare the United States to avoid future energy shortages.

Senator Byrd's fight for coal's reemergence in the energy market and his case for the economic security it could bring met with opposition from scientists and environmental researchers who argued that the extraction of coal caused increased air and water pollution. In time, these consequences of the use of coal hastened the industry's demise as companies began to look for cleaner sources of energy that had less environmental impact. Regulations on emissions from coal-fired electricity generation plants further decreased coal's position in the energy market. Late in his life, Senator Byrd acknowledged the need for renewable energy, employing a similar argument to that of the 1960s, painting the need for American energy independence as key for economic stability. Sources: History.com Editors. “Yom Kippur War,” November 9, 2009. https://www.history.com/topics/middle-east/yom-kippur-war. “Energy Crisis.” National Museum of American History, January 10, 2017. https://americanhistory.si.edu/american-enterprise-exhibition/consumer-era/energy-crisis. History.com Editors. “Energy Crisis (1970s).” History.com. A&E Television Networks, August 30, 2010. https://www.history.com/topics/1970s/energy-crisis. By Patrick Fuller, Byrd Center Student Intern In the decades following World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union went from being allied against Nazi Germany, to being bitter enemies. Throughout the Cold War, which ensued from 1947 until 1991, technological superiority was critical to maintaining an advantage over the opponent. While Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia were among the most hotly contested regions of the globe during the Cold War, there was one more contested frontier which remained unexplored: space. To keep his constituents informed, Senator Robert C. Byrd began writing a regular weekly news column, Byrd’s-Eye View, in 1961. That year, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin made history as being the first human to fly in space. In Volume 1, No. 16 of the Byrd’s-Eye View, Senator Byrd argued that educational enrichment was necessary if the United States was going to compete with the Soviet Union. After making it clear that the education of young people directly affects the future of the nation, Byrd ended his article with this: “…the price of freedom has never been cheap, and if foregoing some luxuries will spare us tyranny of an arrested society--of ruthless dictatorship and human automation--the price is absurdly cheap!” Yuri Gagarin’s taste of space in April 1961 brought the Soviet Union one step closer to putting a man on the moon. In August of the same year, Byrd wrote another Byrd’s-Eye View article which explicitly addressed the desire to put a man on the moon, a desire which President John F. Kennedy expressed when he addressed Congress three months earlier, advocating for funds for space exploration. In his column dated August 25, 1961, Senator Byrd wrote, “This serious undertaking has come about none too soon, for our total application to this effort may determine whether we remain a first-rate independent Nation, or become part of a totalitarian form of world government. Russian competition in this direction leaves us no alternative.” Not only did the Soviet Union’s ability to put a man into orbit before the United States make the U.S. look technologically lacking, but it opened another front in the arms race. Senator Byrd argued, as many Americans believed, that if the Soviet Union could launch a person into space, they could likewise launch a nuclear missile into space. The race to put a man on the moon continued through the end of the decade, appearing in numerous Byrd’s-Eye View columns. Eight years after Kennedy set the goal of putting a man on the moon, it came to fruition with the Apollo 11 mission. On July 16, 1969, NASA launched Apollo 11, with the goal of landing on the moon, exploring its surface, and returning to Earth. Four days after launching from Cape Canaveral, Florida, Apollo 11 landed on the surface of the moon, where Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin conducted the first lunar walk in human history, lasting three hours. Byrd wrote on February 18, 1970, “All Americans were filled with justifiable pride when our countrymen became the first to set foot on the moon…”

Though the Space Race of the 1960s is often deemed an American victory, it is important to remember that the real victor is unclear. While the United States was the first to put a man on the moon, the Soviets were the first to put a man into orbit, and before that, to launch a satellite into orbit. Nevertheless, the appearance of an American victory was enough to provide the morale boost necessary for the American people to continue socially and militarily fighting the battles of the Cold War, and the fight against communist expansion, an issue that the United States was simultaneously combating head-on in Vietnam. By Patrick Fuller, Byrd Center Student Intern From the end of World War II until the early 1970s, a period of great economic expansion swept across the United States. The American middle class experienced substantial growth and found themselves with extra spending money. With the advent of many time-saving home appliances, many Americans also found themselves with extra time for recreation. Naturally, the excess of time and money led to the desire for travel.

|

Archives |

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|