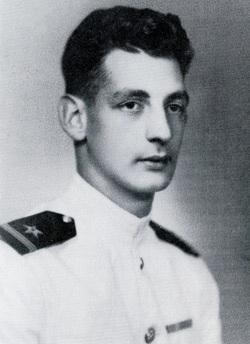

Harlan waited a half century before he told his story in a book published in 1996, All at Sea: Coming of Age in World War II. As he regaled a few of his graduate students with tales of that war and that invasion, we encouraged him to write about it. Who better to tell a story of war than a historian who was there? But he was reluctant to do so because he said he couldn’t trust his memory to tell the story with a level of truth and the degree of accuracy he thought necessary, especially for a historian. While much had been written about that invasion, little was known about the precise history of what happened to the sailors and soldiers on this particular vessel, one tiny speck in the largest invasion armada in the history of the world. Fortunately for those of us encouraging Harlan to write his story, events conspired to give him the kind of historical documentation he needed to do the job. In 1984, forty years after the invasion, Harlan won the Pulitzer Prize for biography for his study of Booker T. Washington. News of Pulitzer Prizes reaches a wide audience. Among them was a long-ago girlfriend who has saved all the letters Harlan wrote to her during the war. She sent him two shoe boxes full of his youthful letters of love and war. Another former girlfriend came forward with more letters. Harlan’s skipper Harold “Cotton “ Clark came forward with his secret diary, kept against Naval regulations, which offered another detailed perspective of the same events. At the National Archives Harlan found the official ship’s log of his craft LCI (L) 555, which covered the full history of the vessel from commissioning to decommissioning. Harlan interviewed Harold Clark and another shipmate Russell Tye. Now he had the confidence to tell the story from memory backed up with documentation. In his letters back home he could not tell what was actually going on due to censorship regulations which prohibited graphic revelations or specific actions. The day after the invasion he wrote only that he was OK and had been in the invasion force. He could not tell, as he later would in his book, of bodies of American soldiers “neatly stacked like cordwood” and used as a barrier for those still trapped on the beach. In one letter home he tried to convey the immensity of it without getting into grim details by writing: “The tale of our latest excursion into the sea is reserved for my grandchildren around a fire on a winter night but I can hint at a few things, such as floating life jackets, air raids, stunned floating fish, a duck with oil on its wings that couldn’t fly, life jackets and K-ration boxes in the water, ships looming out of the fog, and robot planes.”

History and memory are always entwined in complex ways. Louis Harlan had found a way to finally tell a story that had haunted him since the time of that great invasion. Comments are closed.

|

Welcome to the Byrd Center Blog! We share content here including research from our archival collections, articles from our director, and information on upcoming events.

Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed