|

By Jody Brumage On February 11, 1928, Captain Guenette E. Ferguson, the highest ranking Black World War I veteran from West Virginia, addressed a large crowd gathered in the small mining town of Kimball in McDowell County. The audience was assembled to dedicate a new community building for the town that was built as a memorial to African American veterans of "The Great War" and was the first such monument to Black soldiers completed anywhere in the United States. In his remarks, Captain Ferguson gave each of the four massive brick and terra cotta columns that grace the building's classical facade a label: faith, hope, charity, and service. This symbolic gesture expressed the sacrifice of veterans who not only faced the danger and difficulty of serving their nation in the Armed Forces, but did so in the face of racism and discrimination. In 1999, these attributes also came to embody the struggle of a grassroots organization from the community that sought to restore this monument which had suffered decades of neglect only to be gutted by arson. This group persevered and saved a national treasure. Shortly after the end of World War I, Black citizens in McDowell County, located in the heart of West Virginia's southern coalfields, petitioned their county government for funds to erect a community center and war memorial to the over 1,500 black men who served in the war from the county. Under the organization of the Luther Patterson Post 36 of the American Legion, Hassell T. Hicks, an architect from the city of Welch, was commissioned to design the memorial which would be a community center for Kimball. By Allison Wharton, Byrd Center Student Intern The censorship of the internet, particularly on social media, has been a topic of scrutiny and political debate this year. While social media allows for easier spread of ideas and can be used by businesses and professionals for marketing, it is widely regarded as a form of entertainment rather than a medium with any major educational value.[1] The popularity of social media in the 21st century has surpassed traditional forms of media entertainment such as television, but the debate over censorship and the purpose of social media is a continuation of long-standing discussions over the constitutionality of entertainment regulation, which has been addressed by all three branches of government over the past fifty years.[2]

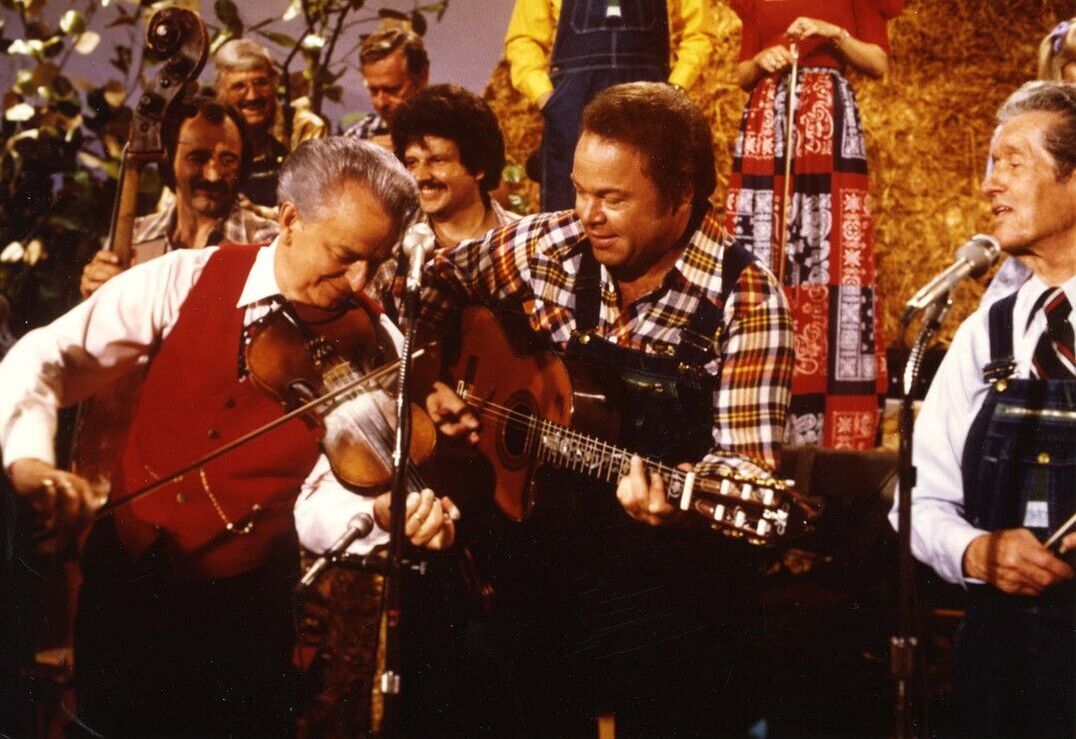

Byrd also wrote about a decrease in crime rates nationally and in West Virginia, and believed that there was an increase in juvenile crime rates that was the product of culture being uncensored and marketed to children. With violence and drug use becoming more common among minors in America, Byrd maintained his stance against television, film, music, and video games depicting crime being marketed to children, arguing for regulations and an updated system of ratings for entertainment deemed inappropriate for young people. Though Senator Byrd was quite vocal about his problems with entertainment media, he also recognized the potential benefits. He believed that television and music would be better used for educational purposes than entertainment. Byrd grew up learning how to play the fiddle, recording an album and frequently playing at public appearances throughout his adult life. While arguing for regulation of the music industry, Byrd did recognize its merit. He also appeared on the show “Hee Haw,” despite his seemingly outspoken opposition to television and argued that a “Family Hour” program was necessary for the entertainment industry because it would provide appropriate forms of entertainment that could also be educational. Senator Byrd was initially lukewarm to the idea of televising floor proceedings of the U.S. Senate when C-SPAN was created in 1979. However, he came to realize the democratizing value that television coverage of the Congress could build and he ultimately became an ardent supporter of allowing cameras into the Senate Chamber in 1986. Byrd’s belief in the regulation of entertainment media was due to his hope for the youth of the country to be better educated rather than to be exposed to themes he cited as the cause for increase in juvenile crime. According to the Federal Communications Commission, material considered “indecent” is protected under the First Amendment and cannot be completely censored.[3] Various members of Congress have spoken both for and against censorship of entertainment and the Supreme Court has a long history of cases on obscenity charges and freedom of speech.[4] Byrd’s reputation as a strict constitutionalist despite rulings to protect entertainment media from censorship reflects the complexity of regulation of the entertainment industry that is still happening today. Social media serves as a form of short-term entertainment, while the shift toward more fact-based and educational usage has the potential to have a larger impact.[5] However, lack of censorship makes the validity of claims more difficult to confirm and potentially allows for the posting of more obscenities, while over-censorship or censorship of free speech would be deemed unconstitutional. The same arguments on social media regulation existed long before in discussion of the censoring of television and music. The debate on social media censorship, fact checking, and algorithmic issues are an extension of larger debates about entertainment that stretch back to the mid-20th century and continue into contemporary discourse. Sources:

[1] Stuart Cunningham and David Craig, Social Media Entertainment: The New Intersection of Hollywood and Silicon Valley, (New York: NYU Press, 2019), 8-11. [2] “A Brief History of Film Censorship,” National Coalition Against Censorship, Accessed June 20, 2020, https://ncac.org/resource/a-brief-history-of-film-censorship. [3] “Consumer Guides: Broadcast, Cable, and Satellite,” Federal Communications Commission, Last modified May 18, 2020, https://www.fcc.gov/general/broadcast-cable-and-satellite-guides. [4] “Freedom of Expression in the Arts and Entertainment,” American Civil Liberties Union, February 27, 2002, https://www.aclu.org/other/freedom-expression-arts-and-entertainment. [5] Brian Patrick Green, “What is the Main Purpose of Social Media: Entertainment or Education?” Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University (blog), December 16, 2019, https://www.scu.edu/ethics-spotlight/social-media-and-democracy/what-is-the-main-purpose-of-social-media-entertainment-or-education/ |

Welcome to the Byrd Center Blog! We share content here including research from our archival collections, articles from our director, and information on upcoming events.

Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed