|

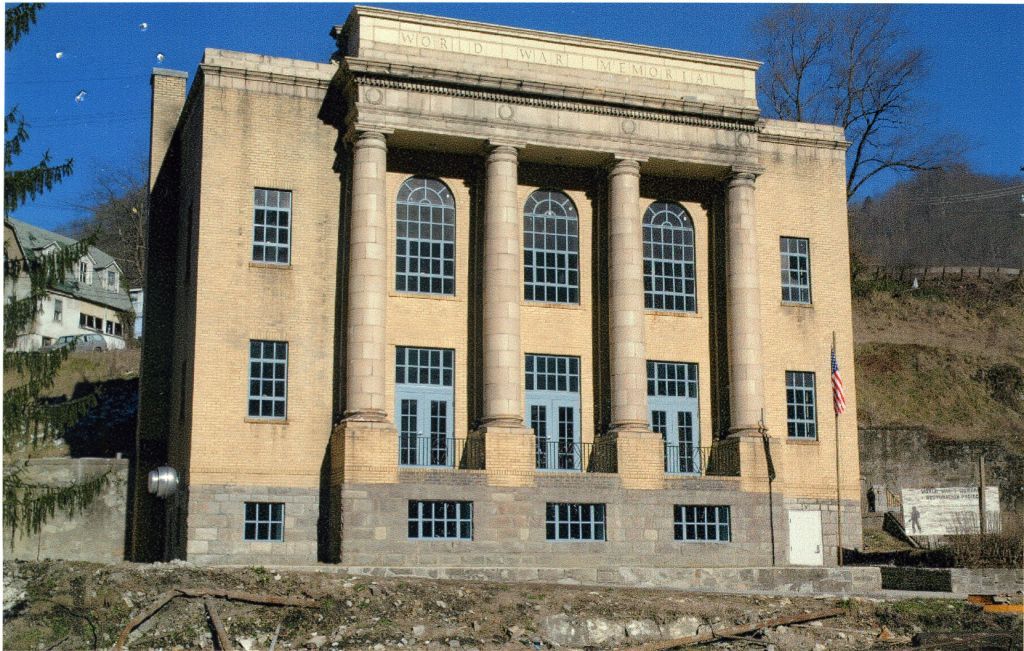

By Jody Brumage On February 11, 1928, Captain Guenette E. Ferguson, the highest ranking Black World War I veteran from West Virginia, addressed a large crowd gathered in the small mining town of Kimball in McDowell County. The audience was assembled to dedicate a new community building for the town that was built as a memorial to African American veterans of "The Great War" and was the first such monument to Black soldiers completed anywhere in the United States. In his remarks, Captain Ferguson gave each of the four massive brick and terra cotta columns that grace the building's classical facade a label: faith, hope, charity, and service. This symbolic gesture expressed the sacrifice of veterans who not only faced the danger and difficulty of serving their nation in the Armed Forces, but did so in the face of racism and discrimination. In 1999, these attributes also came to embody the struggle of a grassroots organization from the community that sought to restore this monument which had suffered decades of neglect only to be gutted by arson. This group persevered and saved a national treasure. Shortly after the end of World War I, Black citizens in McDowell County, located in the heart of West Virginia's southern coalfields, petitioned their county government for funds to erect a community center and war memorial to the over 1,500 black men who served in the war from the county. Under the organization of the Luther Patterson Post 36 of the American Legion, Hassell T. Hicks, an architect from the city of Welch, was commissioned to design the memorial which would be a community center for Kimball. Dedicated on February 11, 1928, the Kimball War Memorial stood equipped with conference facilities, a kitchen, and an auditorium. Artifacts from the war were exhibited throughout the building. Hicks designed the memorial in a restrained Beaux-Arts style, with a large portico of four columns supporting an elaborate pediment upon which the words “World War Memorial” were inscribed. African Americans had resided and worked in coal mines in southern West Virginia since the 1850s, but their population grew significantly after the turn of the twentieth century as a result of the great migration. By 1920, 43% of Black miners in the United States were working and living in West Virginia, mostly in its southern coalfields. However, with the coming Great Depression, a declining market after World War II, and mechanization of the mining industry, the economy that coal had fueled in West Virginia entered a prolonged decline beginning in the 1950s. By the early-1990s, the community of Kimball and its historic War Memorial were struggling along with many other former coal towns across the state. A final act of devastation occurred in 1991 when an arsonist set fire to the Kimball War Memorial, gutting the interior and leaving the building a roofless shell. This act spurred a groundswell of local activism to secure the funds necessary to restore the nation's first war memorial to African American veterans of World War I. They faced a daunting task, with an estimated one million dollars needed to restore the building to its former vitality as a community center. Through the McDowell County Commission, a request for funding was sent to Senator Robert C. Byrd. Citizens began writing letters and sending photographs to the Senator’s office, soon drawing his attention to the project. In response, Byrd added $500,000 to the Fiscal Year 2000 Veterans Affairs/Housing and Urban Development (VA/HUD) Appropriations Bill. In October of 1999, Byrd wrote in a letter to Dr. Sheila J. Brooks, a key leader in the community movement to save the memorial. In it he said: “The Kimball War Memorial is a reminder of the sacrifices made by the soldiers, sailors, and airmen during World War I. It is a unique piece of history, not only to McDowell County, but also to the nation. You may be assured that I am pleased to have supported funding through the appropriations process for this project.”

With nearly $1.2 million in hand, the McDowell County Museum Commission progressed with the restoration, working with photos of the original interior provided by the grandson of Hassell T. Hicks. The Glem Company, of Charleston, West Virginia, oversaw the project. Despite several setbacks, the Kimball War Memorial restoration was completed and opened for community use in the summer of 2006. The newly restored memorial contained meeting rooms, offices, a reception area, auditorium, kitchen, and an exhibit area for WWI artifacts. The restoration of the Kimball War Memorial proved a success, with the project receiving an Honor Award of Excellence from the West Virginia Chapter of the American Institute of Architects. The project also garnered recognition from the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Congressional Black Caucus. Today, the memorial is in use as a community center and event space. In addition, through the efforts of Joel W. Beeson, associate professor of Journalism at West Virginia University, a community archives and exhibit documenting the history of African American service to the United States from the coalfields of West Virginia is contained within the memorial. The exhibit, entitled “Forgotten Legacy: Soldiers of the Coalfields,” supplements the memorial’s archives which were lost to the arson that destroyed the interior in 1991. A digital exhibition of the project can be viewed here: www.forgottenlegacywwi.org/. As a significant landmark of the National Coal Heritage Area, the Kimball War Memorial has become a major contributor to the tourism industry in southern West Virginia and stands as a success story for historic preservation. Its very existence is greatly owed to the interest and dedicated work of the local community. The sources for this article are largely from the Congressional Papers of the late Senator Robert C. Byrd, contained within the archives of the Robert C. Byrd Center for Legislative Studies. Other sources include the Forgotten Legacy website, the National Coal Heritage Area website, and the Bluefield Daily Telegraph of Bluefield, West Virginia. All photographs are taken from the Robert C. Byrd Congressional Papers collection.

Comments are closed.

|

Welcome to the Byrd Center Blog! We share content here including research from our archival collections, articles from our director, and information on upcoming events.

Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed