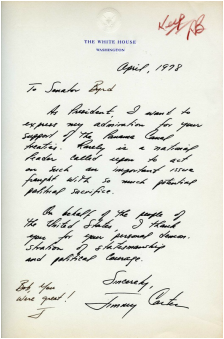

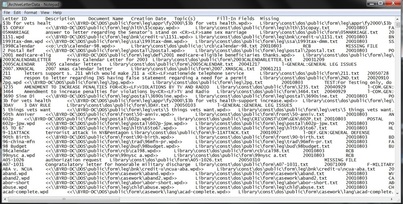

Click to visit their website Click to visit their website Note: This post was previously listed under our "News from the Grey Box" blog series A brief introduction to Congressional records As a repository that deals heavily with Congressional records, this short primer about the different types of records a researcher might encounter will hopefully prove useful to newer patrons. In their daily business, Members of Congress create records that fall broadly into two categories: Committee records and Personal records. Those records created in the business of committees are governed by law (The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946), and have certain restrictions on when they can be open determined by 1) the chamber they originate in (i.e. the Houseor the Senate), and 2) the type of committee (e.g. investigatory or not). Our good friends at the Center for Legislative Archives(a part of NARA) oversee these records and I heartily recommend contacting them if you have research interests in such records.  Congressional records in the Byrd Collection. Congressional records in the Byrd Collection. The “Personal” records of Senators and Congressmen/women are much more varied and have no law governing their disposition. (Incidentally, the Legislative Branch is not subject to FOIA requests, either). Being the sole property of the Member of Congress, these records can be given in whole, part, or destroyed at their will. When such records are donated, it is repositories like the Byrd Center that receive, process, and make available them for research to the public. Similar institutions include the Dirksen Congressional Center, the Carl Albert Congressional Research & Studies Center, and the Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies. In Managing Congressional Collections, Cynthia Pease Miller enumerates over 60 different types of files that can be found in the Personal records of Members of Congress. These include: constituent correspondence, legislative files, telephone call logs, scrapbooks, photographs, flag requests, and many other types of records (we’ll discuss these in more detail in the next post). Though some debate continues about the usefulness of some of these records, everyone agrees that Congressional records as a whole are important for documenting our representative democracy and providing transparency for government activities. In the next post, we’ll discuss the particular types of records in each file group which we hope will help spur your research endeavors! The bulk of Congressional collections is in the form of correspondence, and most of that tends to be from constituents which can broadly be divided into issue files and casework. Issue files, as the name suggests, deals with a diverse range of issues that citizens are concerned about. These range from abortion to welfare and everything in between. Most of the time, the bulk of these issues files come in via form letters from third party websites like AARP, the NRA, or just about any other cause that exists out there. (The anthrax attacks in 2001 coupled with the ubiquity of email has meant that incoming paper mail has been drastically reduced and electronic correspondence has exploded over the past decade or so). Often, the response to issue mail is also handled by form letter, and copies of these responses are also included. Casework from constituents is the other major category of correspondence, and this results from an individual or group of people asking their representative for help with some issue. This can vary from requesting aid in solving a personal matter like Social Security or Veterans Disability benefits to saving a historic landmark in a local town. Such cases require much more personalized attention, first from staff members who liaison with relevant Federal Agencies, and then the representatives themselves. Sometimes people ask for help in issues outside a Congressperson or Senators’ “jurisdiction,” and they are referred to the appropriate agency (known as “Buck” files in our collection). Some requests are much more narrow and at times routine in their scope. Requests for tours, flags that flew over the Capitol, nominations to a military academy, or jobs in the staff office all make it into a representative’s files. And some correspondence is relegated to the “Crank” file which, although more colorful than the average letter, holds little research or historic value (and may not even be answered).  Handwritten letter from President Carter to Senator Byrd (April 1978) Handwritten letter from President Carter to Senator Byrd (April 1978) Correspondence with VIPs (other representatives, presidents, governors, etc.) is often requested and mined by researchers looking for interactions among those in political power. Some, like those with presidents’ signatures, may only be available via a photocopy to protect the original from those who would seek to profit from selling such documents. Another large part of Congressional collections can broadly be termed Press Files. These include not only press releases, speeches, and photographs, but also newspaper clippings, scrapbooks, and excerpts from the Congressional Record (the official transcript of what is said on the House and Senate floors). State and district files often contain casework specific to their areas, as well asProjects that the representative pursues for the sake of their home state. These can be an effort to secure funding for infrastructure improvements, the installation of a new building or agency (and hence the creation of new jobs), or work to preserve historical places or structures. Other records that exist in Congressional collections include the representatives’ schedules, briefing books (issue-related binders prepared by staff members), campaign files, routine office administrative files, telephone logs, staff lists, and visitor logs. Some records that may not be kept by a repository include: duplicate files, publications (that can found elsewhere), and other records that may have been digitized by the archive or a third party. As modern offices move away from paper, many of these records are being incorporated into constituent content management systems (CMS). These systems are complex software and database packages sold and maintained by third-party vendors in Congressional offices, and how these e-records are exported and transferred to repositories is a vital and hot topic right now among archivists who maintain Congressional collections. (You can read about how the Byrd CLS has handled their CMS data in the latest Byrd Call Newsletter, page 8). It should be evident by now that Congressional collections provide a plethora of research opportunities. Not only can one get a sense of how a representative interacted with other politicos, but how they (and their staff) interact with constituents. One can trace the rise and fall of various issues throughout the years, or how some state projects fail or succeed based on the efforts of those involved. I invite you to visit the Byrd CLS to begin your own research project soon!

Comments are closed.

|

Welcome to the Byrd Center Blog! We share content here including research from our archival collections, articles from our director, and information on upcoming events.

Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed