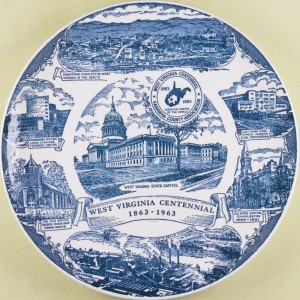

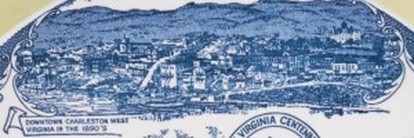

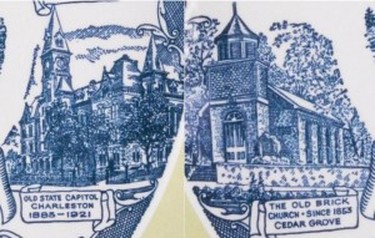

The Byrd Center has been busy this summer as well, and we have begun to take in small collections which will be a part of the Byrd Legacy Series in the Archives. An interesting artifact from one of these small accessions is a commemorative plate, bearing the words “West Virginia Centennial 1863-1963;” donated by Lillian Hill of Shepherdstown. Depicted on the plate are scenes of various buildings and industries which were deemed appropriate to represent the success and character of Kanawha County and the City of Charleston. The plate was produced by the Kanawha County Association for the West Virginia Centennial. After examining each scene depicted on this artifact, an interesting story develops, examining how West Virginia has changed not only in its first century, but now over a century and a half. At the top of the plate is a depiction of Downtown Charleston in the 1890s. The City of Charleston, which has its origins in sporadic settlements and land transactions of the Revolutionary Period, was chartered by the Virginia General Assembly in 1794. Its first period of significant growth was in the early 19th century as area salt mines and coal mines built an industrial complex fueled by the navigable waters of the Kanawha River. At the time that this etching was made of the city’s downtown core, Charleston had grown to a size of around 6,750 inhabitants, but was on the verge of a major expansion, fueled by the industrial revolution. Charleston of the 1890s had recently built a new State Capitol after having the seat of government bounce between Wheeling and Charleston three times. By the state’s Centennial in 1963, Charleston was a city of 85,000 residents. A new State Capitol, featured in the center of the plate, was designed by renowned architect Cass Gilbert. Today, Charleston is a city of 51,400, a little over 30,000 residents short of the high point of the 1960s. A seal just above the center of the plate bears the words “Chemical Center of the World,” reflective of the several large chemical plants that operated and are still present in Kanawha County. These industries, built on minerals such as coal, silica, and salt mined from the mountains of south-central West Virginia, have both enhanced and devastated local economies and the environment. The Belle DuPont Chemical Plant, depicted at the base of the plate, employs over 500 people today, though it has employed upwards of 5,000 people in the past. Established in 1925, Belle Plant was the first commercial ammonia synthesis site. A depiction of the Union Carbide Technical Center occupies one corner of the plate. The company was founded in 1917, and established a factory near Charleston in 1920. Between 1927 and 1932, Union Carbide, in pursuit of silica discovered in a tunneling project, required workers to extract the mineral without protection of masks or respirators. This resulted in over 400 men developing silicosis, a debilitating lung disease, and led to a congressional investigation into the “Hawks Nest Tunnel Disaster.” In 1947, the company built the Technical Center in Charleston which housed research, development, and engineering departments, opening many job opportunities to Charleston and Kanawha County residents. By the 1960s, the factory was producing over 400 different chemicals and plastics, including those used in the production of antifreeze and batteries. Union Carbide was acquired by the Dow Chemical Company which continues to operate its South Charleston Facility today. The last remaining image on the plate is one that reflects a more personal side of West Virginia’s heritage, that of the strong religious community that defined many of its citizens. The “Old Brick Church” of Cedar Grove, built in 1853 by William Tompkins, Jr., is an example of many such churches built by industry leaders for the coal camps and company towns that dotted West Virginia’s hills and hollows. The church, named “Virginia’s Chapel”– after the builder’s daughter–was non-denominational, though it was later used solely by the Methodist Church. Virginia’s Chapel is no longer an active congregation, but the historic building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places for its architectural integrity as well as its symbolism of an important era in West Virginia’s history. At the Byrd Center, artifacts are one in a thousand, but each has the potential to provide a unique insight on West Virginia’s history, a fact of which Robert C. Byrd would be proud. Combined with information collected from an artifacts owner, we built a collection of facts that become an object’s provenance. As we celebrate West Virginia’s 150th Birthday, artifacts such as this commemorative plate enhance our knowledge of the state which Senator Byrd so proudly represented for over 60 years. Sources:

Charleston 175 – The Charleston Gazette, by John G. Morgan (1970) The West Virginia Encyclopedia – West Virginia Humanities Council, Edited by Ken Sullivan (2006) West Virginia Department of Commerce – DuPont Belle Comments are closed.

|

Welcome to the Byrd Center Blog! We share content here including research from our archival collections, articles from our director, and information on upcoming events.

Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed