|

By Jody Brumage In this first blog of a two-part series, we are examining how West Virginia’s senators and congressmen worked to save passenger rail service through the state in the 1970s and 80s.

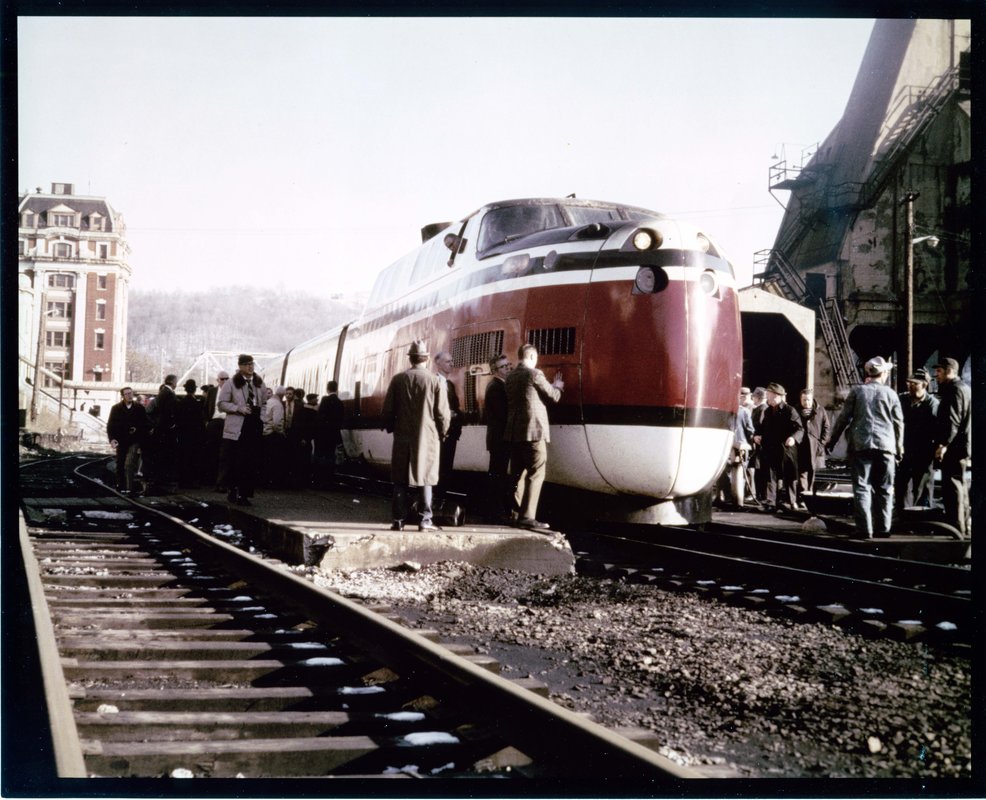

For Congressman Staggers, this news was troubling, especially since the Baltimore and Ohio line extended through a significant portion of his district. His own home town, Keyser, was built by the Baltimore and Ohio and had once been a significant freight and passenger stop on the line. The decision also impacted neighboring Maryland, where the line provided service to the railroad hub of Cumberland. Through his position as chairman of the House Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee, Staggers persuaded Amtrak to reconsider its decision to end rail service through this part of the state. Amtrak acquiesced to Staggers’ pressure and developed the West Virginian, a passenger service line which operated on the Baltimore and Ohio rails connecting Washington DC with Parkersburg, West Virginia. The West Virginian became Amtrak’s first use of the Baltimore and Ohio, one of the nation’s oldest railroad networks, founded in 1827. Critics of the line, citing the declining populations and industries in the region it would serve, labeled the train “Harley’s Hornet” and the “Staggers Special.”

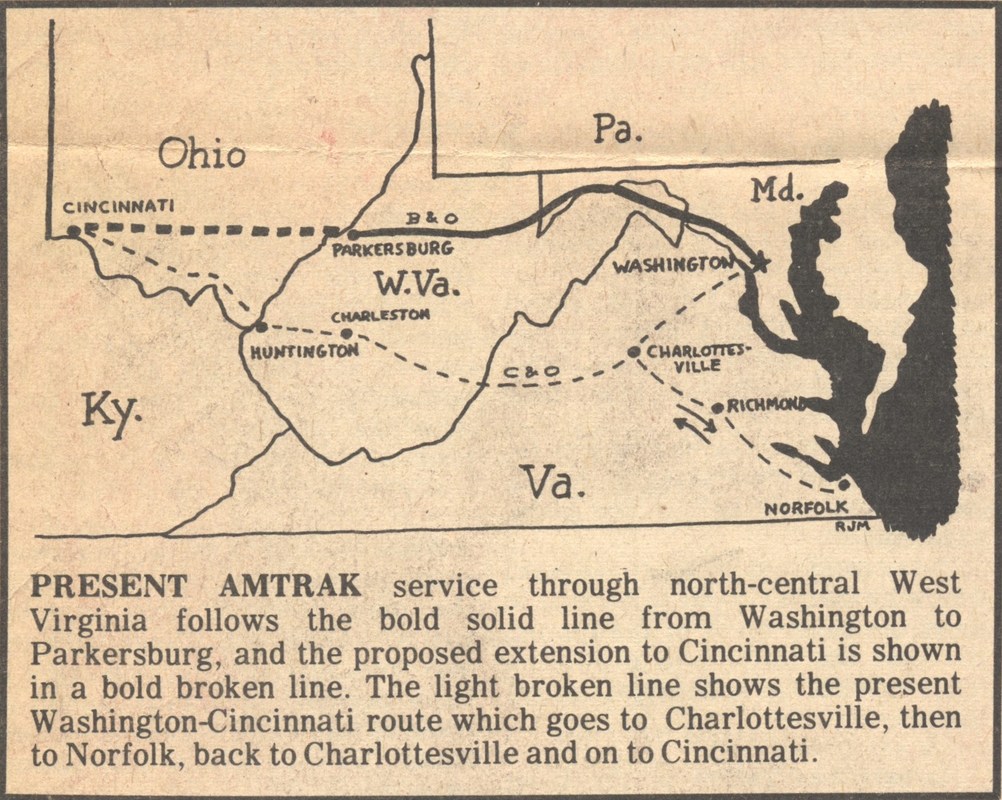

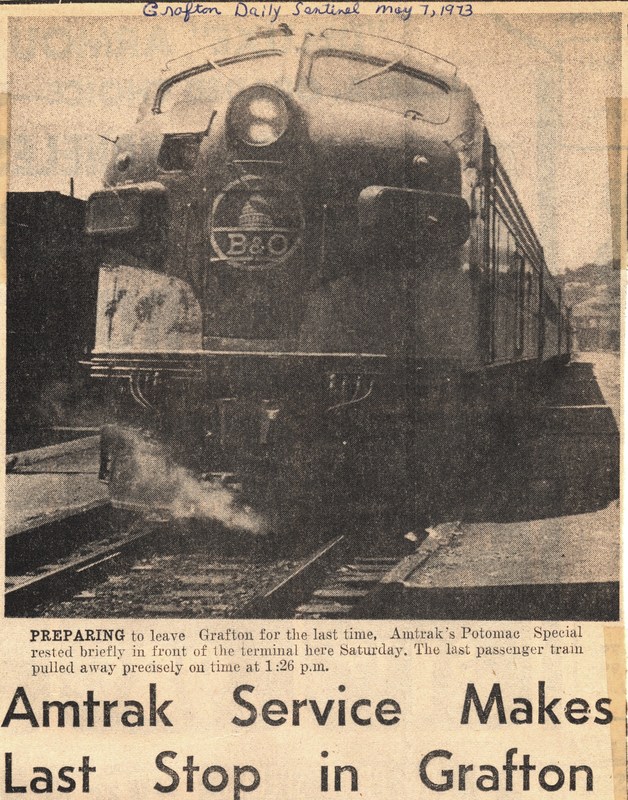

By the spring of 1973, ridership on the West Virginian had failed to meet expectations set by Amtrak and the corporation began discussing discontinuing the line. Congressman Staggers, along with Senators Robert C. Byrd and Jennings Randolph quickly started working to identify sources of funding to save the rail line, including the state of West Virginia and the Appalachian Regional Commission. However, Amtrak had more reasons to discontinue the service than the low ridership. Since its inception, the West Virginian’s ending point of Parkersburg was a point of criticism since no other major lines converged there to provide access to other destinations. Congressman Staggers himself had urged the extension of the line west to Cincinnati, Ohio where other rail lines were accessible. Amtrak declined to do this, fearing that it would jeopardize ridership on another of its passenger service routes which reached Cincinnati via Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad lines (which crossed through south-central West Virginia).

Comments are closed.

|

Welcome to the Byrd Center Blog! We share content here including research from our archival collections, articles from our director, and information on upcoming events.

Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed