|

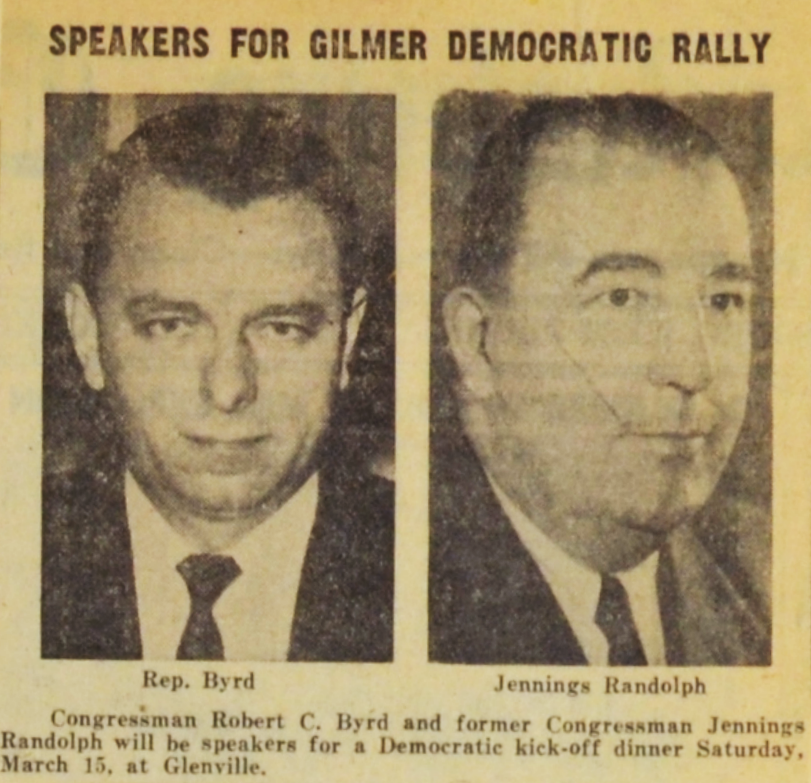

The Byrd Center has received two remarkable documents written by Stan Cavendish that he wrote in 2010, not long after the passing of Senator Byrd in June that year. These are pieces of literature that express marvelously the insights that inspire historians, biographers, political scientists, and anyone wishing to understand the role a senator plays in the life of state and national politics. They suggest to me that we should turn more often to literary forms rather than statistics and policy positions if we want to gain deeper understanding of our elected leaders. Senators Byrd and Randolph came from quite different backgrounds but they campaigned together in 1958 and arrived in the Senate within months of one another. Randolph was elected to fill an unexpired term of two years, so he was sworn in on Nov. 5, 1958. Byrd, running for a full six-year term, was sworn in on Jan. 3, 1959. Thus Randolph was the senior senator from West Virginia until he retired on Jan. 3, 1985. Byrd would go on to set the record for the longest serving senator in American history, serving until his death on June 28, 2010. On behalf of the Byrd Center, I want to thank Stan Cavendish for sharing these wonderful insights with us and with the public. A biographical sketch of Mr. Cavendish follows the two pieces. Ray Smock, Interim Director (Reflection on the service of U.S. Sen. Robert C. Byrd) The Harbinger A hill boy, plain as a mile of dirt road, I can see you there, in the solitary hills, an orphan always looking to belong. But not in this place, surely not in this museum of democracy. You arrived from backwoods where pints of whiskey were more highly valued than points of law; it was democracy of a different strain. You might win over the people with a fine Labor Day speech and a fiddling tune, a square dance call and a prayer for the working man, because you were one of them, with their hard lives, hard needs, hard ideas. But here, you were out of place like muddy boots in marble halls. Yet you became a master of the house where you never belonged – of use, of service, remembering the numbing detail of ledgers, budgets, rules, as though the Thanatopsis recitation was at stake. Forgetting nothing, in particular the haughty tones of your betters, you took a lunch at your desk, soda crackers and dark yellow cheese, while secretaries pushed at you letters to sign, notes with directions to the folks back home – how to find help with the roads, with the Social Security, with the County, when they, like you, had been ignored. While the men with push and pull went to dine at white tables with the company men who hung around the well, you read the books, the history, the law until you could recite them in your dreams. Mansfield and Ervin and Kennedy drove the ship, but you were the quiet rudder. You practiced oratory, sometimes with logic and passion like the preacher sweating and swirling through Daniel and Nicodemus, and sometimes with heavy history, self-important, granddad stories – to a room of yawning clerks. But when the bleak days came, and sharp words were needed, suddenly you stood like Billy Sunday, delivered the Constitution to the brotherhood, shamed them, looked them down, gave them Orwell and Daniel Webster and Ecclesiastes, to the last one, words inspired not by Latin, not Cicero and Caesar this time, but by McGuffey, the mountains and home – stand up straight, work before supper, truth and duty before everything! It is remarkable, not that you arrived in this unlikely place or arrived in an imperfect state, but that you were there for a particular moment when you were needed, a universe away from the butcher shop and the hills, and yet so near – harbinger, a dark bird with a sharp and angry call, the rain crow once again howling down the rain. (Reflection on the service of U.S. Senator Jennings Randolph, with fictional voice of Sen. Robert Byrd) The Common Man How could this be a noble thing, I thought with misgivings when I arrived, to spend your day in argument? To carry no lunch pail, but to wear a woolen suit, suspenders, a tight collar. To have another man at your elbow, shuffling your papers for you, pointing you to a next appointment, quietly and with too much deference. Hands grow soft – how could this be a noble thing? Unless, like you, you were born to wear ruffles at your wrist, and a nanny tied a bow for you just so. And they named you for a famous man without concern for what you might feel need to live up to, because he was a family’s friend who chucked you under your chin, they told you, when you were a gurgling baby. Then, maybe, what else might be expected? Then, maybe, because you are accustomed to hear the rhythm of speech of men who talk in practiced ways at a calm pitch, never causing alarm, you can rise among them and quietly use those words that stir the pots of financial lore and pick the bones of war and commerce, can speak of laws and policy that could move armies, cities, mountains. But how did you know, then – without rough days at school among common men – what the people might require? How roads might change the destiny of those who live among the mountains, how schooling for modern times might let impoverished children awaken to a hopeful day? Perhaps it was something you read, or heard from others’ talk, because you could not have had it in your experience, never put your hands upon it, you born of ruffles and well-laid dinners, where a granny wiped the grease from your pink cheeks, and you never felt the bite of cruel hunger. Because we are such simple creatures of habit and memory, how did you imagine the choking dust that comes of mining rock deep under the hills, the dust that enters a man’s lungs and never leaves, that smothers his very soul? Then you rose and spoke about what must be done to protect this working man, this stranger, this somehow brother. How was there sorrow in your words when you told of the black men buried quietly away in a single grave, with no memorial to their labor, their sacrifice, their lives but cornstalks brown and waving, with no apology, no justice? In this college of well-read men, most born like you in privilege, you held up the lamp of the working man and cast a light on what drives all human aspiration – hunger, work, responsibility, knowledge, justice. The man and woman by the wayside of the road were your concern, you said. But how did you know them? When were you ever there, except passing by in the parade? I think of these things you might have learned – the man who gave five talents to his servant, who then went to the marketplace and traded and made five more for his master. From those to whom much is given, much is expected. So I can understand why, in the college of well-fed men who discuss commerce and law, you might have raised the cause of the working man. But unless there was some deep bond, a resonance outside the range of hearing, I simply don’t know how you understood, when you heard it, the cry of men who bore the brunt of hungry children, no jobs, no hope, and who asked for a new deal. Hugh S. (Stan) Cavendish Biography  Stan Cavendish is a West Virginia native, retired telecommunications industry executive and volunteer leader in programs centered on education, cultural affairs and the environment. He is currently vice chair of the Cedar Lakes Foundation, treasurer of the WV Humanities Council and a master naturalist volunteer, primarily in Canaan Valley, where he and wife Carolyn maintain a second home. Cavendish was raised in Ripley and Beckley, WV; obtained a B.A. degree in English from West Virginia University; worked as a teacher and then weekly newspaper editor, before beginning work at C&P Telephone Company in 1976. He completed a 30+-year telephone career with a five-year term as president of Verizon West Virginia. While in positions focused on education and economic development, he led a successful effort (World School) to bring high-speed internet to all the public schools in the state and another (Office of the Future) to bring more than 20,000 teleservices jobs to West Virginia. He also directed Verizon’s support of the Humanities Council’s WV Encyclopedia project and eWV, the on-line version of the encyclopedia. At Verizon, Cavendish oversaw millions of dollars in focused charitable contributions, including many in support of public education, teacher training and higher education programs, and others in furtherance of enhanced 911 capability statewide. He is past chairman of the State Workforce Investment board and the WVU College of Education Visiting Committee; served on the State Community College Board, WV Roundtable, and Discover the Real WV Foundation, among others. He was honored as an outstanding Almnus of the WVU College of Arts and Sciences. Stan and his wife Carolyn, a well-known watercolorist, live principally in Charleston. They have two children and a granddaughter. Comments are closed.

|

Welcome to the Byrd Center Blog! We share content here including research from our archival collections, articles from our director, and information on upcoming events.

Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed