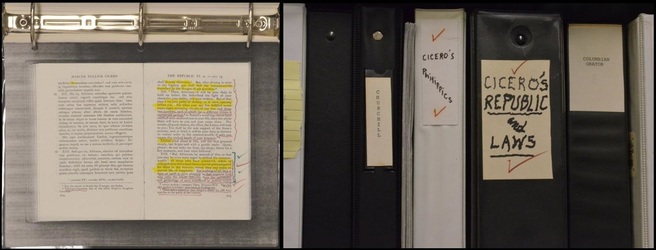

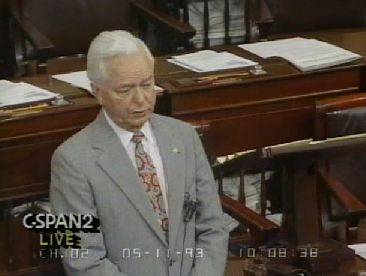

Note: This post was previously listed under our "News from the Grey Box" blog series By Jody Brumage “What is the relevancy of Roman history? To put it simply and elementally, by delivering the line-item veto into the hands of a president – any president, Republican or Democrat or Independent, the United States Senate would have set its foot on the same road to decline, subservience, impotence, and feebleness that the Roman Senate followed in its own descent into ignominy, cowardice, and oblivion.” - Senator Robert C. Byrd, June 22, 1993 Senator Robert C. Byrd, beginning in May 1993, delivered fourteen speeches in the Senate on the history of the Senate of the Roman Republic. While these speeches, delivered entirely from memory, gave a condensed history of Ancient Rome, from the foundation of the Republic to the rise of the Empire, Byrd’s larger thesis was always clear. The Senate had allowed the line-item veto to creep back into floor debate, and it was gaining support. President Bill Clinton, who had enjoyed the privilege of line-item veto while Governor of Arkansas, along with 42 other state governors, was asking for such power to be granted to the presidency as well. Senator Byrd believed such a provision meant the end of Senate supremacy over the purse strings of the federal government and, more importantly, the unraveling of the system of checks and balances which enabled the three branches of government to coexist. Senator Byrd saw the line-item veto as an unconstitutional measure. The content of these speeches was not merely thrown together suddenly to address the growing debate on the line-item veto. Though he never considered himself a professional historian, Byrd had been conducting exhaustive research on the history of Rome for years. In his mind, the Constitution of the United States had been inspired by the writings of enlightenment philosophers and theorists, namely the French philosopher Montesquieu, who is credited with the idea of checks and balances. Yet, as Byrd attested, Montesquieu himself was inspired by English institutions of parliamentarianism and the separation of powers, which in turn had pulled from examples drawn from Ancient Rome. The Robert C. Byrd Congressional Papers contain hundreds of binders containing photocopied books ranging from Cicero and Plutarch to Montesquieu and Jefferson. Collectively, these books were Senator Byrd’s private research library, and they are laden with underlining, bookmarks, and marginalia. Byrd clearly outlined his research methodology in the first of his Roman Senate speeches when he remarked “If he studies history as it bridges the centuries of time, he then becomes the recipient, the beneficiary of the wisdom of hundreds of lifetimes stretching back into the dim mists of antiquity. That is why we are told to study history.” Click here to view a handwritten draft on the thirteenth speech. Reading through the published collection of these speeches, one finds an impressive scope of historical events and figures which Byrd employed to weave his narrative. In his second speech, Byrd notes that the development of the Roman Consulate, where two elected executives shared power for one-year terms, led to the birth of checks and balances, as one consul could veto the actions of the other. In the third speech, the idea of the veto, then claimed by the Roman Senate, enabled the legislature to remain supreme amid the ever increasing layers of bureaucracy that were being added to the Republic. In the eleventh speech, Byrd notes that the Roman Senate developed the idea of filibuster as a measure to postpone a vote on consulship for Caesar, which took place in 60 B.C. The similarities between Rome and the United State were not limited to the rise of power and prestige, but also included the threats which arose to unseat authority and transition the state to a new era which radically changed the definition and structure of the government. In Byrd’s examples, when the Roman Senate began to act hastily to confront crises in the state, throwing its allegiance behind an emergent leader, the seeds of its downfall were sown. One major example cited by Byrd was that of Sulla, who had built his allies in the Roman Senate before asking for the position of dictator to be given an unlimited term. Once he had cemented this executive position, his “appointees to the Senate were beholden to Sulla.” The main point of the speeches was that once the Roman Senate granted special privileges to a favored few, it became a body sharply divided over partisan ideological lines as each side vied for the approval of their chosen leader. If the United States Senate granted special provisions, such as a line-item veto, to a popular executive, as a perceived solution to a crisis, Byrd said the legislature would be severely weakened. When Rome’s Senate followed this path, it became a puppet to the Emperor. Would such actions in the U.S. Senate lead to a further shift in power from the legislative to executive branches of government? Senator Byrd’s speeches ended in October of 1993, each having been covered by C-SPAN, and within the next year, a volume of the collected speeches was printed by the U.S. Government Printing Office. The speeches did not only ruffle the feathers of the opposition, but brought criticism from the public and even his constituents. In one letter, written during the summer of 1993, a constituent questioned Byrd’s prerogatives in giving the speeches and expressed that they were a waste of the Senate’s time. Byrd responded with a blunt defense of the project: “I am making the statements to demonstrate to other Senators and to the public watching that we tamper with our carefully crafted system of checks and balances at our peril. Rome fell when its Senate became weak and ceded its power to a dictator.”

In the twenty years since Senator Byrd gave his speeches on the rise and fall of the Roman Senate’s supremacy, the story of the U.S. Senate has seen great transition in its own right. While the executive branch has yet to gain the privilege of the line-item veto, it came close with the passage of the Line Item Veto Act of 1996. The law was overturned in the case of Clinton v. City of New York of 1998. Despite this decision, two major pushes, in 2006 and 2009, have unsuccessfully attempted to grant a line-item veto to the executive. The events of the past several months, and the 16-day government shutdown, have again brought up questions of the power of the Congress and the relationship between the branches of government. In an era with increasingly bitter partisan rhetoric and floor debate, it is hard to ignore Senator Byrd’s premonition of the results of Congress granting unprecedented powers in times of crisis, lending further relevance to the senator’s work. In the fourteenth and final speech on the Roman Senate, Byrd defended the structure of the U.S. Constitution as the best bulwark for the future success of the government of the United States. “The survival of the American constitutional system, the foundation upon which the superstructure of the republic rests, finds its firmest support in the continued preservation of the delicate mechanism of checks and balances, separation of powers, and control of the purse, solemnly instituted by the Founding Fathers. For over two hundred years, from the beginning of the republic to this very hour, it has survived in unbroken continuity. We received it from our fathers. Let us as surely hand it on to our sons and daughters.” You can view a few of the speeches on C-SPAN’s online archive. Comments are closed.

|

Welcome to the Byrd Center Blog! We share content here including research from our archival collections, articles from our director, and information on upcoming events.

Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed