|

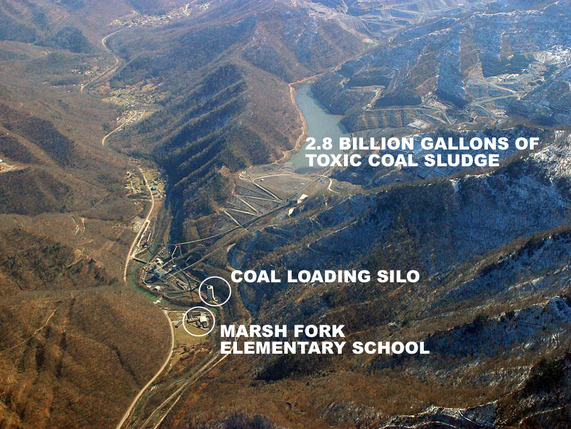

Note: This post was previously listed under our "News from the Grey Box" blog series By Sarah Brennan Throughout his long career, Senator Robert C. Byrd was known for his vocal support of coal miners and their communities. The senator often argued on behalf of the coal industry in front of Congress, but he also frequently introduced and backed legislation that impacted mining families, such as the Black Lung Benefits Act, clean coal technology, and the Mine Safety and Health Administration. It was in this vein that Byrd came to the aid of the residents of Sundial, West Virginia, a small coal town whose lone elementary school sat perilously below a 2.8 million gallon slurry pond containing the toxic liquid byproduct of cleaning coal, and within a few hundred yards of the Goals Coal processing plant. Slurry contains heavy metals and carcinogens, and in the event of dam failure, it poses a serious flood threat. In addition to the fear of the slurry impoundment failing, the school’s proximity to the processing plant was also an issue. Several Marsh Fork children complained of respiratory problems, and tests taken at the school and the surrounding area showed that the coal dust was negatively impacting the students’ health. Headaches and severe coughing fits were common complaints among the children. Concerned West Virginians contacted Senator Byrd regarding conditions at Marsh Fork as early as 2001. Because public schools in West Virginia have been traditionally regulated at a state level, Byrd brought the matter to the West Virginia Division of Environmental Protection (WVDEP). The senator requested a thorough investigation of the slurry impoundment along with a report of any findings. WVDEP officials found that, despite seepage around the dam, “the impoundment has been constructed and is maintained in accordance with federal and state laws.” For the next five years, West Virginians together with Sundial community members fought to have the school relocated, even though they received little help from state representatives. Protests, petitions, and demands did not have much success. Then governor, Joe Manchin, promised a “multi-agency investigation” of the site, but Coal River Mountain Watch representative Bo Webb insisted that hazardous chemicals and dust were not tested for inside the school. The danger that the elementary school faced was once again brought to Byrd’s attention by Ed Wiley, grandfather of a Marsh Fork student. In 2006, Wiley walked from Charleston to Washington, D.C. in order to meet with the senator and raise awareness about the situation in Sundial. Wiley met with Byrd, whom he described as “an honorable man and a true Appalachian,” to make his case against Massey Energy’s treatment of the people of Sundial. The men talked and prayed, and Byrd assured the former Massey Energy contractor that he would do everything within his power to alert the appropriate federal agencies to Marsh Fork’s situation.

In October 2009, after discovering that federal funding would not apply to the construction of a new Marsh Fork Elementary, Byrd released a scathing statement to the press holding Massey Energy directly responsible for the wellbeing of the students in the school. “Let me be clear about one thing – this is not about the coal industry or their hard-working coal miners. This is about companies that blatantly disregard human life and safety because of greed. That is never acceptable.” Senator Byrd’s record indicates that he was decidedly coal friendly. Since 1954, the senator fought for the rights of coal miners and the industry in general in front of Congress, but it was clear that the situation in Sundial required immediate action. In his initial statement, Byrd said: “Such arrogance suggests a blatant disregard for the impact of [Massey Energy’s] mining practices on our communities, residents and particularly our children. These are children’s lives we’re talking about… This is not the taxpayers’ burden to remedy. This is Massey Energy’s responsibility to address.” Massey responded in a press release saying that they were shocked by Byrd’s comments because the senator had not contacted any of the company’s representatives to inquire about their safety record. However, the press release mentioned very little about the slurry impoundment other than to say that it was inspected and that “no concerns have been identified.” According to Massey, the company made many improvements at the facility, including a new silo that reduced the amount of coal on the ground, which in turn reduced the amount of coal dust from handling and wind. The facility’s thermal dryer was shut down, eliminating emissions, belts replaced trucks that drove past the school every day for the transportation of coal and refuse, and chemicals used at the plant were common in the industry and tested and approved by the Environmental Protection Agency and Mine Safety and Health Administration. These improvements did not include any mention of improving the dam that held back the slurry pond, however. Massey claimed that Byrd’s remarks were unjustified and unfair because the Raleigh County School Board had not requested the company contribute any funds for the relocation of the school. Massey’s corporate representative also explained, the “most upsetting comments from Senator Byrd were those regarding our alleged blatant disregard for human life and safety because of greed.” He assured the media outlet that the company’s objective was to improve not only the safety of the miners, but the community as whole. Unbowed, the citizens of Sundial continued pressuring Massey Energy by raising public awareness of the problems the children at Marsh Fork Elementary faced. With Senator Byrd’s help, Massey Energy was finally held accountable for their practices, and they contributed $1 million toward the construction of a new school. The new Marsh Fork Elementary School was dedicated on January 18, 2013, well out of the way of any potential accidents at the coal mine. Sources: Byrd, Robert C. Child of the Appalachian Coalfields. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2005, 68. Coal River Mountain Watch. “The Story (so far) of Marsh Fork Elementary School.” Web. www.crmw.net. Accessed February 25, 2014. Constituent Correspondence, Robert C. Byrd Collection, Robert C. Byrd Center for Legislative Studies, Shepherdstown, WV, 2001-2006. Flynn, Rebeka. “Unequal Education: How Brown v Board of Ed. Decision can be Applied in Rural West Virginia.”International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences. July 1, 2011. EBSCOHost. Web accessed on Nov. 25, 2013. Huber, Tim. “Massey ‘surprised’ by Byrd’s criticism.” Charleston Daily Mail. October 9, 2009. Huber, Tim. “Byrd, others blast coal company over school,” Record Delta, Buckhannon, West Virginia. October 12, 2009. Lydersen, Kari. “A School in Coal’s Shadow,” The Pogressive, January 2007. Web.www.progressive.org/lydersen0107.html. Accessed February 25, 2014. Mountain Justice.” Group says WV Governor broke promise on Marsh Fork Elementary.” Mountainjustice.org.http://mountainjustice.org/2005/10/group-says-wv-governor-broke-promise-on-marsh-fork-elementary/ (accessed March 12, 2014). Roselle, Mike. “March for Marsh Fork Elementary,” Lowbagger. September 18, 2006. Web.www.lowbagger.org/edwalk.html. Accessed February 25, 2006. White, David. “Massey pledges $1 million for school.” Charleston Gazette. March 24, 2010. Comments are closed.

|

Welcome to the Byrd Center Blog! We share content here including research from our archival collections, articles from our director, and information on upcoming events.

Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed