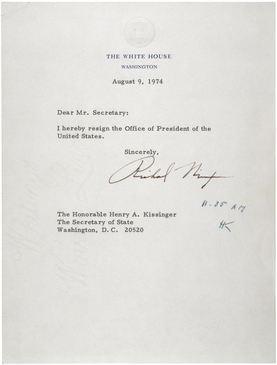

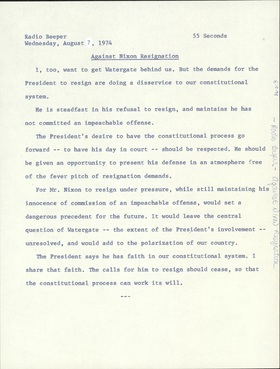

President Nixon’s letter of resignation, addressed to Henry Kissinger, Secretary of State. Note Kissinger’s initials and the time he received the letter. National Archives. President Nixon’s letter of resignation, addressed to Henry Kissinger, Secretary of State. Note Kissinger’s initials and the time he received the letter. National Archives. By Ray Smock Saturday, August 9, 2014 is the 40th anniversary of the resignation of President Richard M. Nixon, the only United States president to ever resign his office. He was about to be impeached by the House of Representatives, and on July 30, 1974, the House Judiciary Committee voted overwhelmingly by a vote of 27 to 11, with six Republicans voting with the majority party, to bring articles of impeachment to the floor of the House for the president’s direct involvement in the cover-up of a burglary of Democratic Party headquarters in the Watergate complex in Washington, DC. Anyone who was not at least 18 years old and following politics in 1974, and this includes a vast number of Americans born after 1956, may have a hard time appreciating the gravity of this major Constitutional crisis and how agonizingly slow it was for the full story to unfold. This crisis came in the middle of the presidential election of 1972, and near the end of the long and costly war in Vietnam that tore the nation apart. The burglary of the offices of the Democratic National Committee headquarters occurred on June 17, 1972, but there was no immediate connection to the president or the White House. That November President Nixon was re-elected in one of the greatest landslides in electoral history. Readers of the Washington Post saw this story unfold through the reporting of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein and others who doggedly pursued the connections of the burglars to the White House and eventual to the President’s involvement in the cover-up. Millions of Americans watched the drama unfold in televised congressional hearings headed by the wily and brilliant Senator Sam Ervin of North Carolina, carried by the major networks in this pre-C-SPAN era. Senator Robert Byrd played a key role in the Watergate saga by turning a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on the confirmation of a new FBI director into an early salvo connecting the White House to the Watergate cover-up though his interrogation of L. Patrick Gray, during Gray’s nomination to be head of the FBI in March 1973. Gray, a Nixon loyalist and political ally, had become acting director of the FBI following the death of J. Edgar Hoover in May 1972. Senator Byrd questioned the wisdom of having a partisan like Gray as head of the FBI, especially when it was Gray who was overseeing the Bureau’s investigation of the Watergate scandal. In Stanley Kutler’s book The Wars of Watergate (1990), Kutler said “Byrd proved to be a formidable antagonist, a rather ironic twist given his previous friendly relations with the President. … Byrd’s questions were devastating. They involved Gray’s political speeches; his political uses of the FBI; his conduct of the Watergate investigation; and his personal handling of evidence from E. Howard Hunt’s safe. The performance was a model of congressional interrogation—so incisive, in fact, that Byrd’s substantive material and questions bore the mark of having originated in the FBI itself.” (Wars of Watergate, 269-70). In David Corbin’s recent book , The Last Great Senator : Robert C. Byrd’s Encounters with Eleven U.S. Presidents(2012) the author describes Senator Byrd’s role in the Gray hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee in even greater detail, making the important connection that Byrd’s interrogation of Gray elicited from Gray a statement that John Dean, the White House counsel, had “probably lied” to the FBI over the matter of whether E. Howard Hunt, one of the Watergate “plumbers” had an office in the White House complex. Gray admitted that he shared FBI information on the Watergate investigation with the president’s counsel. This led Byrd to demand that John Dean be called before the Senate Judiciary Committee to explain himself. Byrd brought John Dean into the glare of the Watergate investigation. When President Nixon refused to allow Dean to testify, Senator Byrd took to the floor of the Senate in a fiery speech to denounce the president for his abuse of executive privilege. In John Dean’s new book, just out this month, The Nixon Defense: What He Knew and When He Knew It (2014)Dean says that Byrd’s interrogation was based on “misinformation,” but nevertheless proved to be effective in dooming Gray’s nomination. Using the recently released Nixon tapes at the National Archives, Dean describes the White House conversation between President Nixon and his Chief of Staff, H. R. Haldeman. The President asks “So what’s your judgment as to how Gray is handling himself?” Haldeman replies, “Dean says he’s not doing well. He is letting too much out….” Dean wrote that Senator Byrd “was taking such a strong anti-Gray position that Haldeman himself was less certain.” (Nixon Defense, 256). In a footnote Dean describes a conversation after the hearings, where Gray admitted to Dean that he “screw-up” in the testimony when he said Dean lied to the FBI. Gray said he would correct the record but he never did. (Nixon Defense, 299). David Corbin cites several reporters at the time, including Carl Rowan of the Chicago Sun-Times, who wrote that Byrd “flushed out the first hints of the Watergate cover-up.” ( Last Great Senator, 141). One reporter, Clark Mollenoff, Pulitzer-prize winning journalist with the Des Moines Register said Byrd was the “unsung hero of Watergate.” ( Last Great Senator, 142). Senator William Proxmire of Wisconsin said the same thing on the floor of the Senate on May 3, 1973, just months after the hearings on the Gray nomination. There is no direct evidence I know of that connects Senator Byrd with any leaks or private information he may have received that made him such a formidable and informed interrogator at the Gray hearings. Stanley Kutler suggests that it appeared as if the information came from the FBI itself. Is it possible that Senator Byrd or someone on his staff was visited by Deep Throat, the FBI informant who helped keep reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein on the trail of the cover-up? Mark Felt was the FBI deputy director at the time of Gray’s nomination hearings. He resigned from the FBI just two months after Senator Byrd’s interrogation of Gray. It was not until 2005 that Mark Felt publically revealed that he was the FBI informant known as Deep Throat. Whether or not Senator Byrd received tips or guidance from an FBI source regarding his line of questioning at the Gray hearings, it is just as likely that Byrd’s insights came from his usual good preparation for a major hearing like this one. Senator Byrd worked harder and prepared better than many senators for hearings and for other committee work. David Corbin explained in his book that Byrd ordered his staff to collect Gray’s many political speeches on behalf of Nixon, and to gather as much evidence as they could. The Senator’s Judiciary Committee staffer, Tom Hart, arranged all the information on Pat Gray into binders and also prepared a card file of information for the senator. Byrd, according to Corbin, “spent hours reading, studying, and memorizing Hart’s binders.” (Last Great Senator, 135). We do know that throughout his career Senator Byrd did his homework. He seldom left the Senate at the end of the day without a binder or two of briefing material under his arm. We have in our collection dozens of his binders containing books on Roman history that he used to write his book on the Senate of the Roman Republic. We have other briefing material, hearing transcripts, and Senate bills, showing how he underlined passages, made marginal notes, and carefully prepared himself to be an effective and productive member of the United States Senate. So far we have not found any of the briefing material that Senator Byrd used during the Gray hearings. But we are always finding new things in Senator Byrd’s personal files, and it is possible that such material resides in the official files of the Senate Judiciary Committee in the National Archives.  Senator Byrd’s radio beeper concerning the calls for Nixon’s resignation. Robert C. Byrd Congressional Papers Senator Byrd’s radio beeper concerning the calls for Nixon’s resignation. Robert C. Byrd Congressional Papers Senator Byrd did not want President Nixon to resign. He believed the constitutional process of impeachment should run its full course even if the process would add to the polarization of the nation. Just a day before President Nixon informed the nation that he would resign on August 9, Senator Byrd issued a radio statement on August 7 calling for talk of Nixon’s resignation to cease. Byrd was not trying to save President Nixon, just give him the due process he deserved under the Constitution. Nixon’s resignation cut short the constitutional process of impeachment and left the nation with questions we are still trying to answer forty years later. President Jerry Ford was sworn in as the 38th President of the United States within a half hour of Nixon’s resignation. He announced to the nation that “our long national nightmare is over.” He also said “Our Constitution works.” Everyone at the time was relieved that the agonizing, drawn out process was at an end. Nixon’s resignation brought immediate relief of the political tensions of the time. But it was only a temporary relief and we are left with the troublesome precedent that a president can be driven from office before the constitutional process is carried through to its conclusion. Still, it was the threat of impeachment, the bipartisan vote of the House Judiciary Committee that made impeachment in the House and conviction in the Senate virtually a forgone conclusion. In this important sense, the Constitution did indeed work. The evidence against the president from audio tapes he made and refused to destroy was overwhelming. It was far more than a smoking gun. Comments are closed.

|

Welcome to the Byrd Center Blog! We share content here including research from our archival collections, articles from our director, and information on upcoming events.

Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed