|

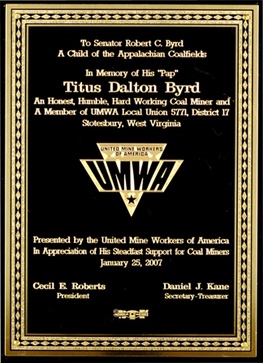

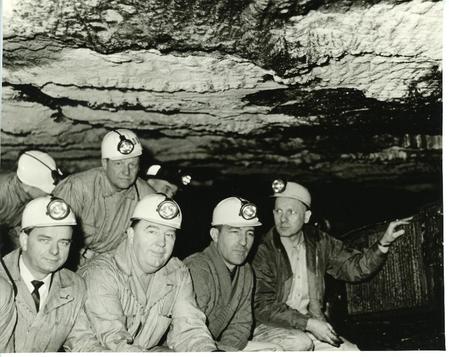

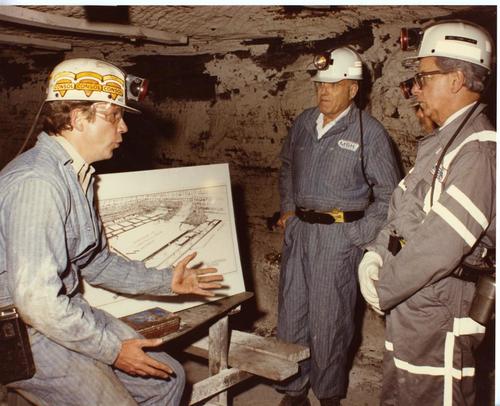

Note: This post was previously listed under our "News from the Grey Box" blog series By Christopher Taylor  In January 2007, United Mine Workers Local Union #5771 recognized Senator Robert C. Byrd’s “steadfast support for coal miners,” with a plaque in the name of his father, Titus Dalton Byrd, himself a coal miner. From lobbying the President to earmarking federal dollars, Senator Byrd worked hard to improve the lives of West Virginia coal miners and their families throughout his political career. Senator Byrd’s family, like thousands of others in southern West Virginia, lived in a coal company town, Stotesbury. Byrd recalled that the coal company “touched the miners’ lives at every point,” and that its influence was “complete” and “ruthless.” In addition to the mine, the company owned virtually the entire town, from the miners’ houses to the church. Stotesbury’s only store was company run. Miners and their families purchased household goods there with company scrip—tokens which were only redeemable at that store. In those days, dissent was settled by mine guards who administered punishments ranging from evictions to “bloody scenes.” Growing up in such conditions left Senator Byrd with an immense appreciation for the plight of coal miners and their families. As a young man, Byrd was inspired by the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration’s progressive reforms, particularly the legalization of labor unions. Byrd praised the unionization of the coalfields as the culmination of the miners’ “long history of struggle and deprivation.” Other Depression-era reforms included state and federally-mandated improvements in mine safety and health standards, an end to the mine guard system, and the prospect of collective bargaining for miners. Senator Byrd “came to understand not only how government works, but that government does work.” As a Senator, Byrd put his influence to use when coal miners again fought for their rights in the late 1960s. Conditions had improved in the mines over the years, but change was not necessarily all positive. Years of increased mechanization (and the finer coal dust produced by machines) led to a generation of coal miners suffering from pneumoconiosis, or black lung disease—a debilitating and often fatal lung condition similar to silicosis. In 1969, a grassroots effort on behalf of coal miners resulted in legislation for the compensation of black lung victims passing the House and Senate. Although President Richard Nixon’s cabinet urged him to veto the bill, successful lobbying by Senator Byrd prompted him to sign it into law. Three years later, Senator Byrd’s own Black Lung Benefits Act aimed to streamline and expand the earlier legislation by “providing faster service, better assistance, and clearer medical definitions of various black lung related health problems.” This measure was also signed into law by Nixon despite unanimous cabinet opposition. Here again, this was largely due to Senator Byrd’s efforts. After Byrd’s persistent phone calls and telegrams, Nixon staffer Clark MacGregor remarked that Senator Byrd was someone who would “not be put off.” Later, as unemployment skyrocketed among West Virginia coal miners during the 1980s and 1990s, Senator Byrd fought vigorously on their behalf. Byrd invoked the miners’ wellbeing frequently on the senate floor. In 1989, he opposed Senator George Mitchell’s clean water legislation (with its call for the significant reduction of coal burned in power plants), arguing that it would be devastating to the coal miners of his home state. Byrd referenced an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimate which forecasted a 35-percent reduction in mining jobs as proof that the bill would affect miners directly, and he explained why he feared the proposed Clean Water Act would plunge the region into dire straits not seen since the Depression. Byrd argued that “for every coal mine job that is lost here, two non-mine jobs are estimated to be lost.” In a region “devastated already” by the nation’s highest unemployment rate and limited economic opportunity, Senator Byrd asked the Senate: “where are they going to get jobs?” Byrd later proposed an amendment which would provide compensation and job training for the miners who would soon be unemployed, but the measure was considered too costly. It was defeated by one vote. As Chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, Senator Byrd’s efforts to improve the lives of West Virginia’s miners met with greater success. The senator used his leadership position to earmark federal dollars aimed at supporting the coal industry and other potential areas of economic growth in the state. Coal industry improvements included research into clean coal technology as well as the establishment of the National Mine Safety and Health Academy (the national training center for mine inspectors) in Beckley, WV. These measures sought to preserve coal mining jobs by making the industry more environmentally-minded while ensuring the miners’ safety. Additional earmarks for parks, military installations, and highways were investments that fostered employment alternatives other than mining. Senator Byrd did not provide a panacea for all the issues facing West Virginia’s coal mining families—but he certainly helped them in every way he could. Awarded just three years prior to his passing in 2010, the United Mine Workers plaque reveals the high regard that West Virginia’s miners held for Senator Byrd and his longstanding advocacy on their behalf. Sources:

Byrd, Robert C. Child of the Appalachian Coalfields. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2005. Corbin, David A. The Last Great Senator: Robert C. Byrd’s Encounters with Eleven U.S. Presidents. Washington D.C.: Potomac Books, 2012. Williams, John Alexander. West Virginia: A History. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press 2001. Comments are closed.

|

Welcome to the Byrd Center Blog! We share content here including research from our archival collections, articles from our director, and information on upcoming events.

Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed