|

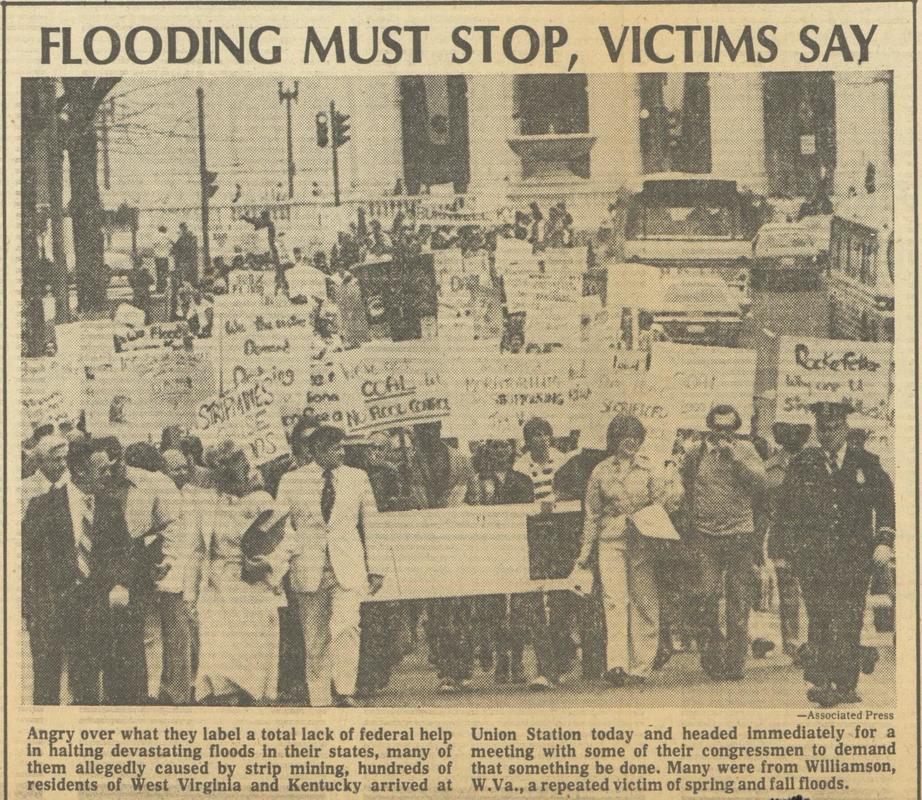

By Jody Brumage Click here to read the first part of this blog series on the Tug Fork Valley Floods. Hundreds of residents of the Tug Fork Valley converged on Washington DC in April 1978. Tired of unfulfilled promises of federal assistance for flood control, they marched to the Capitol to demand that Congress appropriate funding for infrastructure that could tame the Tug Fork River and lessen the impact of future floods. They were addressed by members of their congressional delegation, including Senators Jennings Randolph, Robert C. Byrd, and Congressman Nick Joe Rahall. Three months earlier in January 1978, the Tug Fork once again overflowed its banks and inundated towns throughout the southern coalfields of West Virginia. The previous year, the worst flood in recent memory on the Tug Fork saw over 56 feet of water in Williamson, a city along the Kentucky-West Virginia border. Residents in the state were formed into a committee by the State Legislature in Charleston to make recommendations for solutions to the severe and frequent flooding disasters they faced. Meanwhile, in the nation’s capital, Senators Randolph and Byrd and Congressman Rahall also investigated the problem, trying to determine a way to secure much-needed funding for flood control projects without coming up against a rule stipulating dollar-for-dollar cost-benefit matching. The delegation put together a package of legislative proposals, including putting Tug Fork communities under the National Flood Insurance Program, opening the possibility for business owners to secure loans for rebuilding and protecting their shops. The senators and congressman also called for the appropriation of money to build flood control infrastructure around some of the valley’s most critically-threatened communities. The problem with this proposal was that the Tug Fork Valley could not meet the required cost-benefit ratio mandated for flood control projects. The only way to avoid this obstacle was to gain enough Senate support for the amendment to waive the rule.

With plans drawn up by the Army Corps of Engineers, the total cost for the proposed flood control project, including levees, flood walls, and river channel diversions, was $284 million. The delegation was successful in achieving enough support in the Senate to pass the Tug Fork Valley flood control amendment, avoiding the cost-benefit ratio, but in the House, opponents to the effort succeeded in striking it from legislation three times. Another attempt which passed both the Senate and House ended up being vetoed by the President. On September 9, 1980, Senators Byrd and Randolph again introduced their amendment on the Senate Floor. In his defense of the measure, Byrd declared “four times the U.S. Senate has responded to my plea, along with the requests of my colleague, Senator Randolph, and has provided authorization for extensive flood relief…while I have kept my pledge, the hopes of these people remain unfulfilled.” Randolph added “no matter how badly needed this legislation is, it still has not become law…the people of the Tug Fork Valley have come so close, yet continue to be so far away from the safety and security that all American’s deserve.” These impassioned statements resulted in yet another successful Senate vote in favor of the amendment. Once in the House of Representatives, the amendment was approved in the interest of not jeopardizing the overall $12 billion Energy and Water Appropriations Bill to which it was attached. With the appropriations now available, work began on the long-awaited flood control system in the Tug Fork Valley. In the years since work began on the various components of the massive project, the flood control system has helped to cut-down the frequency and severity of disastrous flooding in the region. As recently as February, the flood wall around the city of Williamson protected its residents from severe damage after the Tug Fork swelled to 36 feet following heavy rains. When staff from the Byrd Center visited Williamson last year with our traveling exhibit, Robert C. Byrd: Senator, Statesman, West Virginian, city residents recalled the 77/78 floods and the sense of safety afforded by the massive flood wall that now wraps around two sides of the city’s downtown. Views of the flood wall (left) and gates (right) at Williamson, taken in 2017 when the Byrd Center exhibit was displayed at First National Bank.

Comments are closed.

|

Welcome to the Byrd Center Blog! We share content here including research from our archival collections, articles from our director, and information on upcoming events.

Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed