|

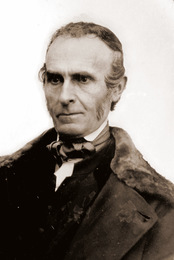

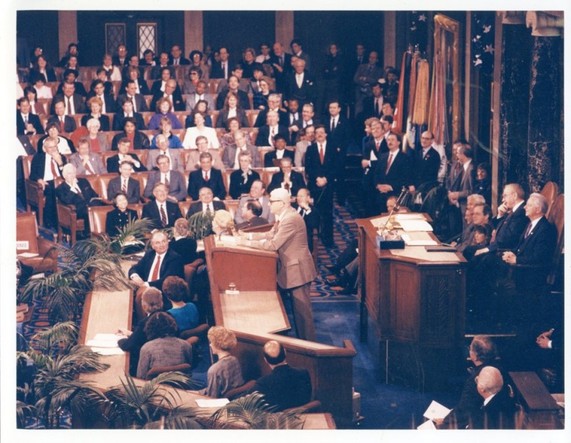

by Ray Smock April is National Poetry Month and the Byrd Center’s contribution to this worthy endeavor is to share a reflection on two poets, more than 100 years apart, who wrote about the Congress of the United States. What follows is taken from the private journal I kept when I served as the Historian of the U. S. House of Representatives. The first poet, John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892) wrote about the Congress that first convened in December 1865. The Civil War was over, Reconstruction was beginning. Congress had a big job on its hands in the midst of tumultuous times. The second poet, Howard Nemerov (1920-1991), the Poet Laureate of the United States in 1989, wrote a poem to commemorate Congress completing two centuries. It was my great pleasure to ask Mr. Nemerov to write this poem and then to ask him to deliver it before a joint meeting of Congress held Mar. 2, 1989. Nemerov became the first poet to ever deliver a poem in person before a joint meeting of Congress. He was the second poet to appear before Congress, the first being Carl Sandburg in 1959, on the 150th anniversary of the birth of Abraham Lincoln. Sandburg spoke to Congress on Lincoln’s life but did not read poetry that day.  John Greenleaf Whitter John Greenleaf Whitter August 15, 1992 From the Private Journal of the House Historian. I ran across a reference to a poem John Greenleaf Whittier wrote about the 39th Congress, which convened in 1865. I thought it would be interesting to see what he said about this Congress in light of my experience with Poet Laureate Howard Nemerov and his offering to the 101st Congress during our bicentennial celebration in 1989. I haven’t read any of Whittier’s poems since I was in school but I found it most interesting. Some of the lines are as relevant today as they were then, even though the circumstances have changed dramatically. The style of the two poems also contrast nicely, as one might expect of words written more than a century apart in what were essentially different worlds. The thing they have in common, aside from the subject of Congress, is that both poets recognized the centrality of Congress to the political process, and also its fragility. Here is the Whittier poem. TO THE THIRTY-NINTH CONGRESS The thirty-ninth congress was that which met in 1865, after the close of the war, when it was charged with the great question of reconstruction; the uppermost subject in men’s minds was the standing of those who had recently been in arms against the Union and their relations to the freedmen. O PEOPLE-CHOSEN! are ye not Likewise the chosen of the Lord, To do His will and speak His word? From the loud thunder-storm of war Not man alone hath called ye forth, But He, the God of all the earth! The torch of vengeance in your hands He quenches; unto Him belongs The solemn recompense of wrongs. Enough of blood the land has seen, And not by cell or gallows-stair Shall ye the way of God prepare. Say to the pardon-seekers: Keep Your manhood, bend no suppliant knees, Nor palter with unworthy pleas. Above your voices sound the wail Of starving men; we shut in vain Our eyes to Pillow’s ghastly stain. What words can drown that bitter cry? What tears wash out the stain of death? What oaths confirm your broken faith? From you alone the guaranty Of union, freedom, peace, we claim; We urge no conqueror’s terms of shame. Alas! no victor’s pride is ours; We bend above our triumph won Like David o’er his rebel son. Be men, not beggars. Cancel all By one brave, generous action; trust Your better instincts, and be just! Make all men peers before the law, Take hands from off the negro’s throat, Give black and white and equal vote. Keep all your forfeit lives and lands, But Give the common law’s redress To labor’s utter nakedness. Revive the old heroic will; Be in the right as brave and strong As ye have proved yourselves in wrong. Defeat shall then be victory, Your loss the wealth of full amends, And hate be love, and foes be friends. Then buried be the dreadful past, Its common slain be mourned, and let All memories soften to regret. Then shall the Union’s mother-heart Her lost and wandering ones recall, Forgiving and restoring all,– And Freedom break her marble trance Above the Capitolian dome, Stretch hands, and bid ye welcome home! Whittier’s poem had a very specific message given the time and the circumstances. The nation had to heal its war wounds. Whittier, following the idea if not quite the eloquence of Abraham Lincoln, hoped the nation could come together with malice toward none. He had lost none of his earlier abolitionist fervor when he wrote “Make all men peers before the law,/Take hands from off the negro’s throat,/Give black and white an equal vote.” He appealed, however, to the members of the 39th Congress to avoid retribution. His reference to “Pillow’s ghastly stain” was to urge Congress to remain cool during its investigation of Confederate atrocities at Fort Pillow, Tennessee. When that fort was recaptured by Confederate forces, under command of Nathan Forrest, later founder of the Ku Klux Klan, supposedly black soldiers were murdered after they surrendered. I assume Whittier was among those who believed, along with many members of Congress, that atrocities did occur at Fort Pillow, even though no final resolution of the matter was ever made. Whittier ends with a marvelous image of the Statue of Freedom, placed on the dome of the Capitol during the Civil War, breaking “her marble trance” and stretching her hands to welcome home all Americans under the dome of the Union. Whittier was either unaware of the composition of the Statue of Freedom, or chose to employ literary license. The statue is made of bronze, not marble. But the word bronze does not fit the meter of the poem and marble does. It is still a wonderful image. The poem urges the Members of the 39th Congress to respond to a higher calling. He begins by calling them the “People-Chosen,” and then reminds them that perhaps it was God who chose them to heal the nation. The first four stanzas reinforce the role of God in their work. Typical of Whittier’s style and that of the time, the poem has a few “O’s” and “Alases,” four question marks, and three exclamations in its fifty-two lines, not counting the preface.  When I turned again to Howard Nemerov’s poem I was struck by its resemblance to Whittier, partly in form, and more so in general theme, even though Nemerov arrives at his conclusions from a different perspective all together. If Howard was still alive I would pick up the telephone as ask him if he looked at Whittier before he sat down to compose his poem. Both poems begin with a narrative preface, a bit unusual in itself. It almost seems as if Howard was nodding to a colleague who had taken up the subject before him. But this superficial similarity is not to suggest that Nemerov was particularly influenced by Whittier. Whittier’s poem began “O People Chosen!” and Nemerov says in his preface: “Because reverence has never been America’s thing, this verse in your honor will not begin ‘O thou.’ But the great respect our country has to give may you all continue to deserve, and have.” Then, using four-line stanzas rather than three, and in a tightly written work of half the length of Whittier’s piece, which Nemerov titled: “To the Congress of the United States Entering Its Third Century, With Preface.” Here is the poem. Here at the fulcrum of us all, The feather of truth against the soul Is weighed, and had better be found to balance Lest our enterprise collapse in silence. For here the million varying wills Get melted down, get hammered out Until the movie’s reduced to stills That tell us what the law’s about. Conflict’s endemic in the mind: Your job’s to hear it in the wind And compass it in opposites, And bring the antagonists by your wits To being one, and that the law Thenceforth, until you change your minds Against and with the shifting winds That this and that way blow the straw. So it’s a republic, as Franklin said, If you can keep it; and we did Thus far, and hope to keep our quarrel Funny and just, though with this moral: Praise without end for the go-ahead zeal Of whoever it was invented the wheel; But never a word for the poor soul’s sake That thought ahead, and invented the brake. This poem separates church and state. It is devoid of references to God, but it does talk about truth-seeking, justice, and the soul. But the underlying assumptions about the importance of Congress, the fragility of government and the republic is clear in both poems. Whittier said it this way: “From you alone the guaranty/ Of union, freedom, peace, we claim.” Nemerov chose to define the centrality of Congress to the nation by saying, “Here at the fulcrum of us all.” Both poems recognize the passions of humans that must be released and yet controlled in the legislative process. Whittier warned Congress not to let the passions of the just-ended Civil War, or their investigation of war-time atrocities, cloud their vision of justice and fairness to all. Nemerov said unless Congress found a way to balance the passions and conflicting interests of the “million varying wills” we ran the risk of having our whole enterprise “collapse in silence.” I suppose there are other poems written about Congress. Certainly there has been plenty of doggerel verse written about it over the years. I know of at least one rendering of the work of the First Congress, which praised the results of its efforts. That poem appeared in the Gazette of the United States in 1791. But my curiosity has been peeked to see if I can find other poems, not so much the daily doggerel of the press and the pundits, but the serious work of major poets. I will keep an eye out for it. I would like to see someone commission a book of poems on Congress, or even more broadly on American government. I suppose most poets writing today would tend to take a more cynical look at our governmental institutions, but I may be wrong about this. Certainly when I asked Howard Nemerov to participate in the bicentennial of Congress and to read a work before a joint meeting of Congress, I had no idea how he would treat Congress. I never even thought of imposing any requirements on him. It would have been totally inappropriate for me to even hint at his theme. While he was Poet Laureate, he was not being paid to say nice things about the government. He was free to speak his own mind. He could have lambasted Congress. He could have been more critical. Instead he, and Whittier more than a century before him, chose not to praise or criticize Congress. They both took the poet’s role of admonition and warning and of urging Congress to rise to noble purposes because so much was at stake. Both poets assumed Congress was important to the life of the Republic. Both poems recognize the frailty of politicians and the difficulty of harnessing human passions. From time to time the members of Congress, and the people who elect them, need to be reminded of these things by poets and other artists who do not have the same axes to grind as journalists, political activists, or television commentators. Sources:

Whittier, John Greenleaf, The Complete Poetic Works of John Greenleaf Whittier (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1894), 347-48. Nemerov, Howard, Trying Conclusions: New and Selected Poems, 1961-1991 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 142-43. Comments are closed.

|

Welcome to the Byrd Center Blog! We share content here including research from our archival collections, articles from our director, and information on upcoming events.

Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed