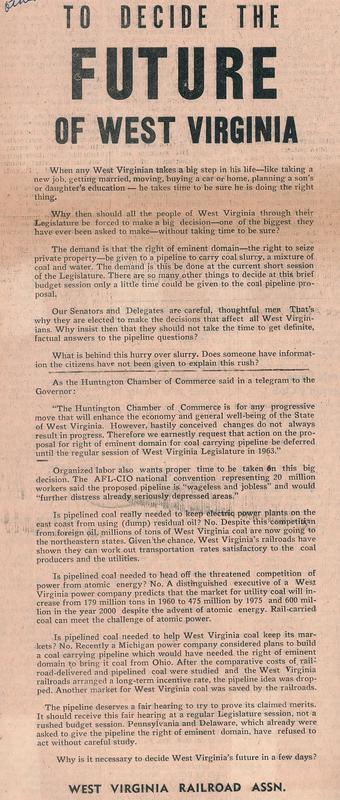

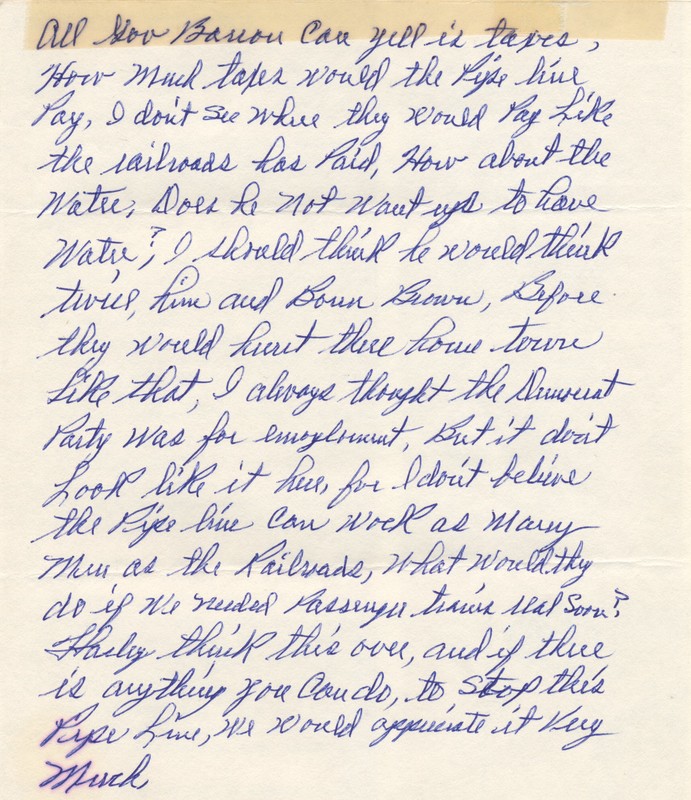

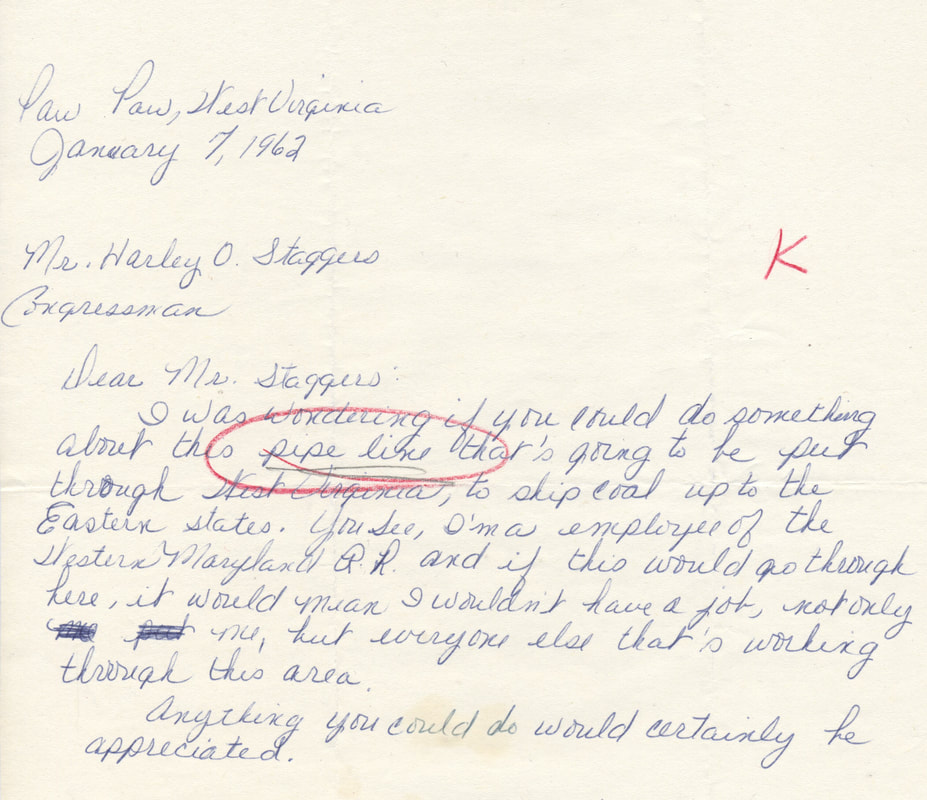

In 1961, Consolidation Coal Company, one of West Virginia's largest mine operators, began planning a pipeline that would open up new east coast markets. However, one major roadblock stood in the way of this idea. In order to clear the pathway for the new pipeline, the company would need to have the project designated as a public work which would give them the right of eminent domain. After this request was made to the state of West Virginia, an intense debate broke out in the state legislature which put the proposal on its agenda for the 1962 session. The coal companies had a powerful ally in West Virginia Governor William Wallace Barron who pledged his support for the pipeline in interviews and editorials published around the state. Many West Virginians however were not completely sold on the opportunities the proposed pipeline was touted to bring. For rail line operators and many residents in the 2nd Congressional District, where important railroad depots like Elkins, Keyser, and Grafton were located, the proposed pipeline was a significant threat to the railroad's monopoly on coal transport. Fueled by newspaper advertisements and pamphlets expressing intense opposition from railroad companies like the Western Maryland and Baltimore and Ohio Railroads, citizens in the 2nd district wrote their Congressman, Harley O. Staggers, Sr., asking him to step in to prevent the pipeline in any way he could. While he noted in his replies that the matter was at that time being considered in the state legislature where he had no authority or power, Congressman Staggers, a long-time ally of the rail industry, expressed his opposition to the pipeline. As West Virginia’s Legislature debated the idea of granting the right of eminent domain to the coal company for their pipeline, President John F. Kennedy urged Congress to set a federal policy that would grant coal pipeline operators the power of eminent domain to clear the pathways for their projects. While the powerful coal lobby was winning the battle for the pipeline in West Virginia's legislature, the rail lobby in neighboring Virginia, through which the pipeline would have to cross, was having equal success in defeating the proposal in their state legislature. President Kennedy's efforts on the national stage didn't fare much better as the bill never left committee in the Senate and wasn't taken up by the House.

The battle over the pipeline pitted many powerful groups against each other in West Virginia. The United Mine Workers of America supported the proposal as a way of strengthening the coal industry in the state while the railroad workers union opposed the threat to rail's stronghold on coal transport business. The pipelines opponents raised questions over the merit of deeming the project of one specific company (Consolidation) a "public" work and also expressed concern over the environmental impact the pipeline might have, such as the amount of water that would be needed to successfully implement the system. When the federal legal battle over the question of eminent domain was lost, the company abandoned its project in West Virginia. However, other slurry pipelines have been built in different parts of the United States and as recently as 2004 accounted for the third largest share of coal transport behind rail and trucking. Comments are closed.

|

Welcome to the Byrd Center Blog! We share content here including research from our archival collections, articles from our director, and information on upcoming events.

Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed