|

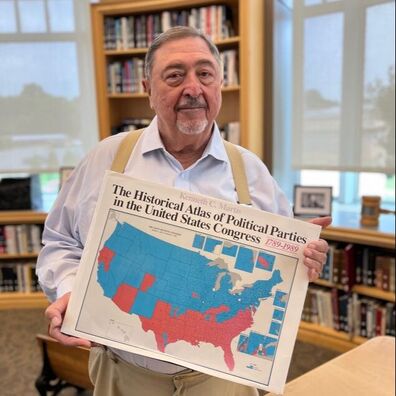

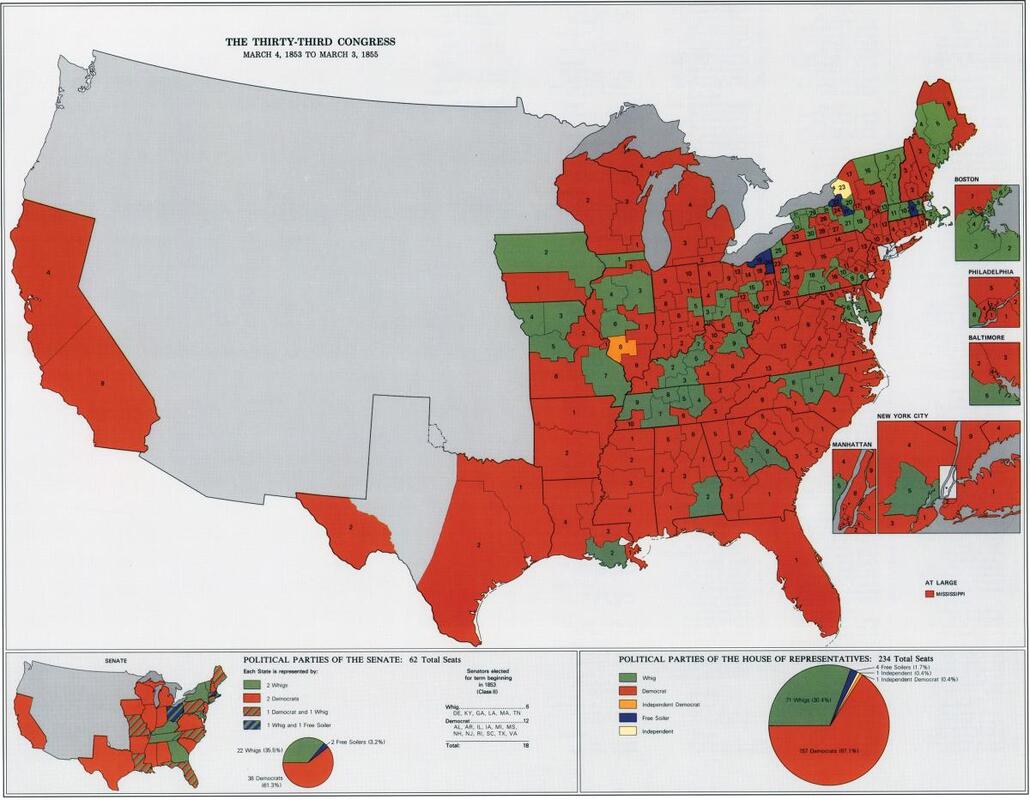

By Ray Smock When I was the Historian of the U.S. House of Representatives, I was fortunate to meet up with a political geographer from West Virginia University, Dr. Kenneth C. Martis. He was working on an incredible project to map every Congressional election beginning with the First Federal Congress in 1789. This involved researching more than 30,000 elections. His work, The Historical Atlas of Political Parties in the United States Congress, 1789-1989 is a seminal work in America political history. We have a copy here at the Byrd Center if you ever want to explore the rich and complex history of political parties spread across national maps of the United States. At the same time Martis was working on his project, my office and the Senate Historical Office were preparing a new edition of the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774-1789: Bicentennial Edition. This massive volume contains biographies of more than 11,000 persons who have served in the House and Senate during its first two centuries. We has many opportunities to share our information with Martis, and he, in turn, was able to help us correct many errors from earlier editions of the Biographical Directory. The Senate Historian Richard Baker and I wrote a forward to Martis’s work and participated in a program at WVU when the atlas was published. We also helped arrange for a major bicentennial exhibition of Martis’s work at the Library of Congress. All this is preface to the article by David Skinner from the summer issue 2023 of Humanities: The Magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities, where the work of Ken Martis, is “rediscovered” in a story well told. I hope you will read along about this remarkable work of scholarship, whose significance has not diminished with the passage of time. The full article from The Magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities is available HERE.

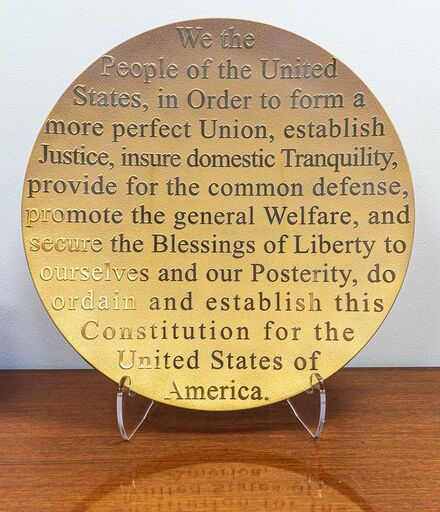

By Ray Smock This is a story about the Preamble to the Constitution that I am telling now to give some context to a donation that my wife Phyllis and I have just made to the Byrd Center. We have long admired a fine piece of glass artwork displayed from time to time at the Shepherdstown, West Virginia shop Dickinson & Wait, which features beautiful art and crafts by American artists. This piece, a large circular plate with the entire Preamble to the Constitution in gold letters is by the California artist Stephen Schlanser, whose work is in the private collections of well-known public figures and world leaders. It was Phyllis who said to me this past weekend, “We have admired this piece for so long, it is time to get it and donate it to the Byrd Center.” I heartily concurred! I have long thought that the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution is the very best single sentence ever written that explains the purpose of government. It is fifty-two words in length. You could build an entire academic course around it, or use it to introduce young school kids about why we have government and what that means. And, you can even sing it! More about this later. The wording of the Preamble to the Constitution was not debated at the Federal Convention of 1787, and it does not have the legal authority that the text of the document does. It was pretty much a flourish, an introduction with little meaning when compared with the body of the document. There was nothing unusual about the idea of having a preamble. This was common practice in England and that practice came to the New World. An earlier famous preamble, the one to the Declaration of Independence in 1776, takes up most of the document. We do not learn until the final paragraph that it is a declaration of independence and the end of colonial allegiance to the British crown. That preamble contains the stirring words: “We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness….” After the debates of the Federal Convention neared conclusion in August 1787, Delegate Edmund Randolph of Virginia made the point that the Constitution was a legal document, not a philosophical one and therefore it was not necessary to have a preamble that dealt with the philosophy of the structure of the new government they were about to establish. So the early draft of the preamble began “We the People of the States of….” Then followed a list of each individual state. This draft ended with the phrase: “do ordain, declare and establish the following Constitution for the Government of Ourselves and our Posterity.” Without much thought, the delegates unanimously approved this draft. When the Constitution and its preamble went to a final Committee on Style just nine days before the delegates would approve the document, Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania, rewrote it and made it into literature and philosophy. He changed “We the People of the States of…” to “We the People of the United States….” There was no need to mention the states individually. Then Morris added six specific goals that described what the Constitution, and therefore, what Government itself was about: to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty. This remarkably revised Preamble and the body of the Constitution was approved on September 17, 1787. Edmund Randolph who was instrumental in defining the purpose of the Preamble was one of three delegates who refused to approve the Constitution that day. He was against it because it did not have a bill of rights and he thought it gave too much power to the executive branch. The Preamble is important as a philosophical concept of what government is for, and what it should achieve for the people of the nation. It is so easy to get lost in the specific issues and circumstances of any particular point in American history that we sometimes need to return to the Preamble as a touchstone and ask ourselves, how well we are doing in the six broad areas of purpose. Now, to return to my reference about singing the Preamble. On the 200th anniversary of Constitution in 1987, it was my job as the first official Historian of the House of Representatives and as director of the Office for the Bicentennial of the House to plan, in conjunction with my Senate colleagues, major commemorative events. One of the biggest was an excursion of a large contingent of House and Senate members via a special Amtrak train, to Philadelphia for the convening of special sessions of the House and Senate on the grounds of Independence Hall, where the Constitution was drafted and approved. Earlier during the bicentennial, my friend Franklin Roberts, a Philadelphia producer of historical events, had created a production with a troop of singers and actors (including one portraying Ben Franklin) who told the story of the drafting of the Constitution in song. It was called “Four Little Pages.” It was a popular presentation at National Parks and other venues during the bicentennial years. I was so taken with this show that I wanted the Representatives assembled in Philadelphia to allow the troop onto the floor to sing the Preamble as the finale of our session. And, I wanted the Members of Congress, and the Speaker of the House, Jim Wright of Texas, to sing along. Speaker Wright was reluctant when I first presented the plan to him. I took a video tape of the performance to his private office and he watched it with interest. But he wondered if the dignity of our ceremony, and the solemnity of the speeches that day would be undercut by a troop of singers. He told me to have the actors assembled outside the chamber, and, if, at the last minute, it seemed right to him, he would give me the nod and I could bring the troop in. At the very last moment the Speaker looked over to me and gave me the OK. I nodded to an assistant nearer the door, and the singers were ushered in. As the Speaker announced some “special guests” the troop came in and after formally bowing to the Speaker and the members, and they won the chamber over. Listening to the members of the House of 1987 singing the words of the Preamble drafted 200 years earlier, was one of my best moments as House Historian. I will think of that moment, and all that these 52 words mean to this nation every time I pass this lovely work of art. May it inspire those who see it to reflect on the meaning of government. By Ray Smock

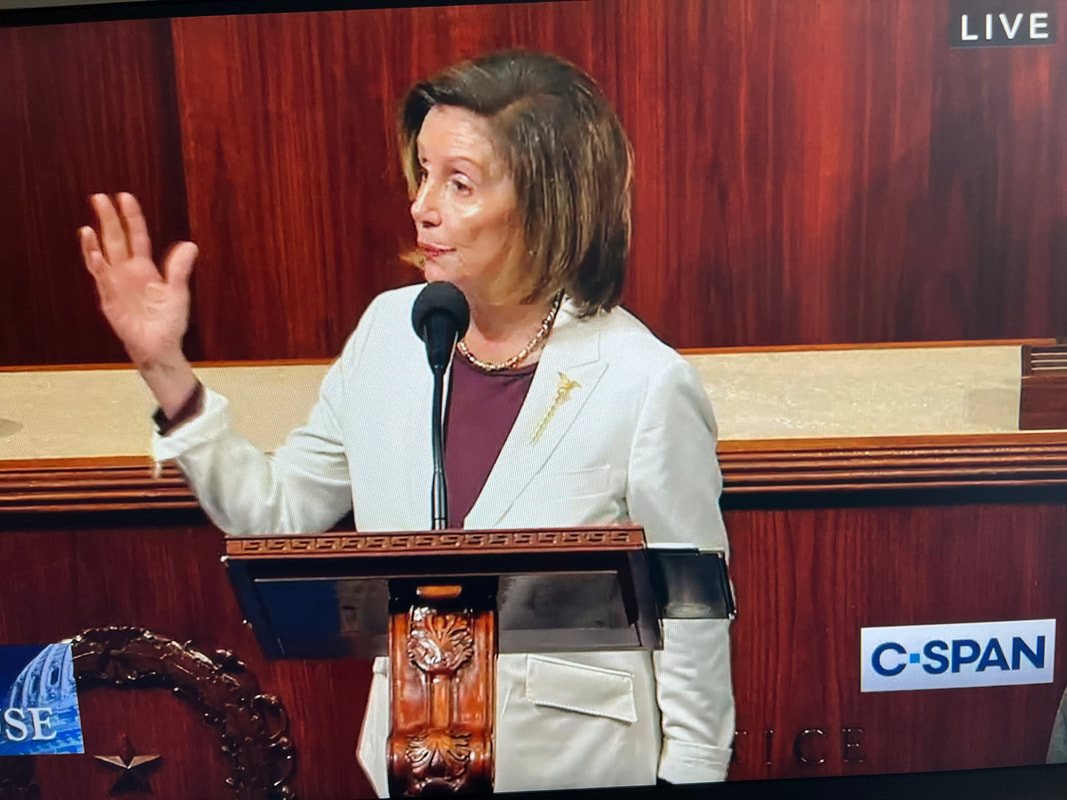

I am happy to report that the $1.7 trillion Omnibus bill just passed and signed into law contains $2 million for competitive grants related to the processing and preservation of Congressional Papers. It was twenty years ago that the Byrd Center hosted a meeting of congressional scholars, current and former members of Congress, and others to form a new association: The Association of Centers for the Study of Congress (ACSC). I served as its first president, and later Jay Wyatt, my successor as Director of the Byrd Center, also served as president. There are about 50 organizations nationwide that specialize in archives related to the papers of former members of the House and Senate. The Byrd Center contains the congressional papers of five West Virginia members of Congress, the Senate Papers of Robert C. Byrd, and the House Papers of Harley Staggers, Sr, Harley Staggers, Jr., Robert Mollohan, and Alan Mollohan. Collectively the Byrd Center contains a rich story of West Virginia and national political issues covering more than 60 years. Many of us in the ACSC have long sought a regular appropriation for the preservation of these collections so they could be made available for public research. It has been fourteen years since Congress passed H. Con. Res. 307, which stated that members of the Senate and House should save their papers and make them available to the public for research. It is a neglected part of our national documentary heritage. While some collections have been funded over the years through earmarks, (and I am certainly not opposed to seeing them continue), preserving these collections should be recognized as essential to telling the story of American representative democracy. This $2 million will be administered by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, an independent agency affiliated with the National Archives and Records Commission. (NHPRC). It will be up to the NHPRC to develop a competitive program and announce it to the public. I hope this will be the beginning of regular appropriations for this purpose. Congress remains the least studied of the three branches of government. The material in the Byrd Center and in other such places across the country represent a national treasure of state and national history, and the raw material for many research projects, books, and biographies. By Ray Smock I was the House Historian in 1987 when Nancy Pelosi first entered the House of Representatives. I witnessed her rise to leadership. She said in her speech today that she went from "homemaker to House Speaker." This is true but it does not tell the full story of her long involvement in American politics, which was a family calling with her father serving in numerous political offices including Congress and later as Mayor of Baltimore. She was no ordinary freshman member in 1987. She hit the ground running. Nobody worked harder in the House than did Nancy Pelosi. I have studied the speakership and leadership in the House and I had the honor of working for three Speakers: Thomas P. "Tip" O' Neill, Jr. of Massachusetts, Jim Wright of Texas, and Tom Foley of Washington State. Nancy Pelosi is the first woman to hold this job and she clearly ranks as one of the best and most effective speakers in American history. Past speakers from both parties have sought to represent their party and also the nation. Some have been negative forces holding back the future and clinging to the past. This negative role was sometimes what the country seemed to want, as was the case at the turn of the 20th Century, when powerful speaker Joe Cannon of Illinois held up progressive legislation for years saying the country was doing fine and didn't need any new legislation.

Wielding power alone does not make a leader great. Power does mark and shape the institution and national affairs. Greatness in a speaker, I suggest, comes from a positive role, not a negative one. Greatness stems from a vision of a better future and the effort to improve the lives of the people. In this context Nancy Pelosi qualifies easily as a great speaker. Today she cited the Preamble to the Constitution, still the best single definition of what government is for and should do. Government should establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity. And when Speaker Pelosi got to the word "posterity" she clarified it. It is our nation's children. It is future generations. Children born today, she said, will live into the next century. What kind of nation and what kind of world do we want to leave to the children? She will stay in Congress and represent her San Francisco district. I am sure she will continue to be force in the affairs of her party and the nation. But today she passed the torch of leadership to a new generation. It is so in her character of looking forward.

This totem was created for President Joe Biden “to raise awareness of Indigenous sacred sites at risk from oil, gas, mining, and infrastructure projects.” The totem was accepted on behalf of the President by the Secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland. The totem traveled more than 25,000 miles before reaching its final destination, stopping at eight endangered sacred sites: Snake River, Idaho; Bears Ears, Utah; Chaco Canyon, New Mexico; Black Hills, South Dakota, Missouri River, South Dakota, Standing Rock, North Dakota, White Earth, Minnesota and the Straits of Mackinac, Michigan. You can watch the dedication ceremony at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7RSmE38DmUs The director of the NCTC, Steve Chase, in his opening remarks, began by acknowledging that the land on which the NCTC sits was once the home of many indigenous peoples including the Shawnee and the Delaware. Those who spoke stressed not only the need to protect sacred sites, but for all of us to be stewards of Earth. Human activity has created a planetary crisis of global warming which affects every person and every nation. As I write this, we are learning of the awful devastation from Hurricane Ian, and I thought back to my own experiences on Pine Island in Florida, one of the places hardest hit. That island too has a long history with indigenous peoples. Perhaps the highest ground on that island is the shell mounds built by the Calusa, the dominant people of South Florida for many centuries. I wonder if that place is still recognizable.

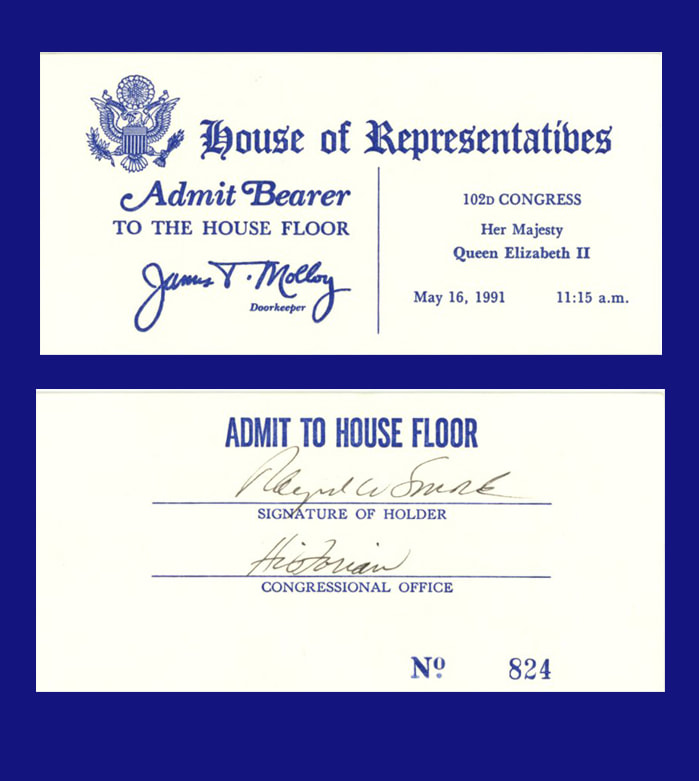

By Ray Smock When I served as House Historian, I was eyewitness to the ceremonial events in the House Chamber. With the passing of Queen Elizabeth today, I offer this account of her only appearance before the U.S. Congress on May 16, 1991. The following are excerpts from the journal I kept during my years in the House. Excerpts from the Journal of the House Historian, May 24, 1991 …The night before the Queen's appearance before the joint meeting of Congress on the 16th I was working late, and Vic Ratner of ABC called to ask a question. "Did we ever send the British a bill for burning the Capitol in the War of 1812?" He apologized for asking; it was clear he was stretching for a story angle. (Later Cokie Roberts told me she put Vic up to it.) I laughed and said to Vic "Why would we send them a bill, we thought we won that war." *** The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh do have a regal and polished bearing from a lifetime of role playing. I was surprised by how short (and wide) she is and how tall he is. The Duke sat in a chair on the Speaker's dais to the left and behind the Queen. Behind him in his usual prominent spot was the Clerk of the House Donn Anderson, who simply loves all this pomp and circumstance. I could tell that he was thoroughly enjoying this setting. My only exposure to the Queen was during the joint meeting. I was in the chamber in my usual spot [standing near the portrait of George Washington] and watched the proceedings. The chamber was packed, but not overly crowded the way it was for Nelson Mandela or Lech Walesa. The Doorkeeper was a little more nervous than usual because he wanted to get their introduction just right. Even the wily old veteran Molloy seemed taken by the opportunity to introduce the Queen, for the first appearance of a British monarch before the U.S. Congress. It was a historic moment, if only a symbolic one. *** The press gallery was particularly animated during the joint meeting, especially when the Queen first entered the chamber and again when she exited following her address. The press sits in the gallery directly above and behind the Speaker. Most of the time there are only a few members of the press seated there for the regular business of the House. During special occasions, however, they fill the seats. Those in the press gallery never show any particular emotion other than mild boredom or amused detachment. They don't stand or applaud when the president or the guest speaker enters the chamber. While all the other galleries rise and engage in applause, as do the Members and staff on the floor. The press, as a show of their aloofness, and to demonstrate the fact that they are busy working and writing, pretend they are not a part of the proceedings. In Don Ritchie's excellent new book Press Gallery he quotes journalist Louis Ludlow of Indiana, a member of the press gallery for more than a quarter century before running for Congress himself: "In the Press Gallery we sit at the top of the world and the kingdoms of earth are at our feet." That captures the attitude that prevails in the press gallery. In reality, however, they are no more detached from what goes on the floor of the House than I am, but both our professions demand the appearance of detachment and impartiality. For the Queen's visit the press leaned forward and strained to see every nuance of her arrival and departure. They reacted just like any other citizen who wanted to glimpse a celebrity. They lost their cool, if only for a moment. As the Queen approached the Speaker's dais and the press had to look almost straight down, I thought half of them were going to tumble out of the gallery and fall on the Speaker, [Tom Foley] the Vice President, [Dan Quayle] and the Queen. Wouldn't that have made a good story and a great picture for the cover of the news magazines. *** There was nothing special about the Queen's address. It was, in fact, very bland, and she read it without much spirit or emotion. I guess queens and popes don't have to be entertaining. They are speaking to the ages. The Queen, of course, is really delivering a message from the British government. She delivers what the Prime Minister wants her to. It was a short speech, politely interrupted by respectful applause on several occasions. Her only display of playfulness and spirit came at the very beginning before she launched into her formal remarks. As she stood at the podium she said, "I do hope you can see me today." This brought down the House and she received a standing ovation and much laughter. The day before when she was received by the President [George Bush] someone screwed up and did not make arrangements for the podium to match her height. It was set for the President who is well over six feet tall. When the Queen came forward to speak all anyone could see was a bank of microphones and her purple hat. She was dubbed the "talking hat" or the "talking mushroom." The Queen’s opening line before Congress was perfect, a real icebreaker. But then her speech was so uninspiring that the ice began to form again almost immediately.

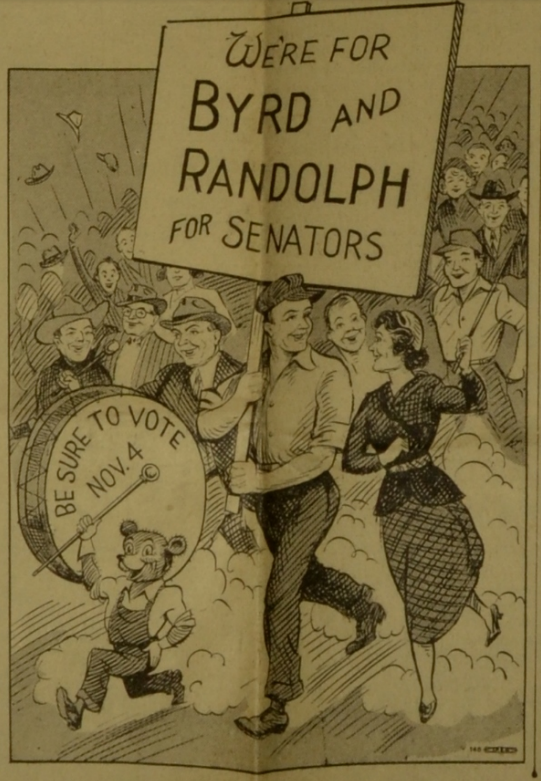

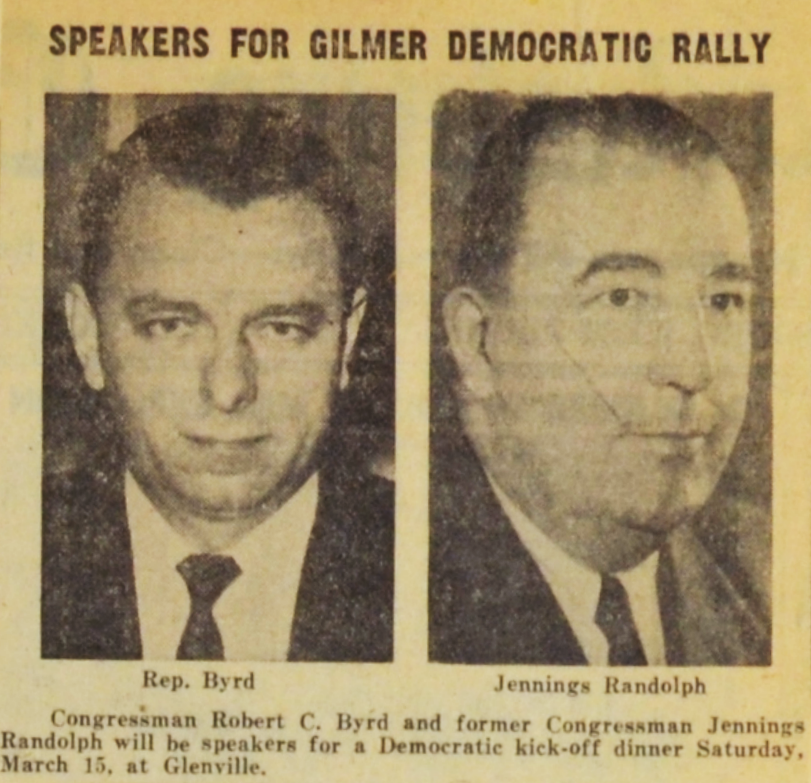

The Byrd Center has received two remarkable documents written by Stan Cavendish that he wrote in 2010, not long after the passing of Senator Byrd in June that year. These are pieces of literature that express marvelously the insights that inspire historians, biographers, political scientists, and anyone wishing to understand the role a senator plays in the life of state and national politics. They suggest to me that we should turn more often to literary forms rather than statistics and policy positions if we want to gain deeper understanding of our elected leaders. Senators Byrd and Randolph came from quite different backgrounds but they campaigned together in 1958 and arrived in the Senate within months of one another. Randolph was elected to fill an unexpired term of two years, so he was sworn in on Nov. 5, 1958. Byrd, running for a full six-year term, was sworn in on Jan. 3, 1959. Thus Randolph was the senior senator from West Virginia until he retired on Jan. 3, 1985. Byrd would go on to set the record for the longest serving senator in American history, serving until his death on June 28, 2010. On behalf of the Byrd Center, I want to thank Stan Cavendish for sharing these wonderful insights with us and with the public. A biographical sketch of Mr. Cavendish follows the two pieces. Ray Smock, Interim Director (Reflection on the service of U.S. Sen. Robert C. Byrd) The Harbinger A hill boy, plain as a mile of dirt road, I can see you there, in the solitary hills, an orphan always looking to belong. But not in this place, surely not in this museum of democracy. You arrived from backwoods where pints of whiskey were more highly valued than points of law; it was democracy of a different strain. You might win over the people with a fine Labor Day speech and a fiddling tune, a square dance call and a prayer for the working man, because you were one of them, with their hard lives, hard needs, hard ideas. But here, you were out of place like muddy boots in marble halls. Yet you became a master of the house where you never belonged – of use, of service, remembering the numbing detail of ledgers, budgets, rules, as though the Thanatopsis recitation was at stake. Forgetting nothing, in particular the haughty tones of your betters, you took a lunch at your desk, soda crackers and dark yellow cheese, while secretaries pushed at you letters to sign, notes with directions to the folks back home – how to find help with the roads, with the Social Security, with the County, when they, like you, had been ignored. While the men with push and pull went to dine at white tables with the company men who hung around the well, you read the books, the history, the law until you could recite them in your dreams. Mansfield and Ervin and Kennedy drove the ship, but you were the quiet rudder. You practiced oratory, sometimes with logic and passion like the preacher sweating and swirling through Daniel and Nicodemus, and sometimes with heavy history, self-important, granddad stories – to a room of yawning clerks. But when the bleak days came, and sharp words were needed, suddenly you stood like Billy Sunday, delivered the Constitution to the brotherhood, shamed them, looked them down, gave them Orwell and Daniel Webster and Ecclesiastes, to the last one, words inspired not by Latin, not Cicero and Caesar this time, but by McGuffey, the mountains and home – stand up straight, work before supper, truth and duty before everything! It is remarkable, not that you arrived in this unlikely place or arrived in an imperfect state, but that you were there for a particular moment when you were needed, a universe away from the butcher shop and the hills, and yet so near – harbinger, a dark bird with a sharp and angry call, the rain crow once again howling down the rain. (Reflection on the service of U.S. Senator Jennings Randolph, with fictional voice of Sen. Robert Byrd) The Common Man How could this be a noble thing, I thought with misgivings when I arrived, to spend your day in argument? To carry no lunch pail, but to wear a woolen suit, suspenders, a tight collar. To have another man at your elbow, shuffling your papers for you, pointing you to a next appointment, quietly and with too much deference. Hands grow soft – how could this be a noble thing? Unless, like you, you were born to wear ruffles at your wrist, and a nanny tied a bow for you just so. And they named you for a famous man without concern for what you might feel need to live up to, because he was a family’s friend who chucked you under your chin, they told you, when you were a gurgling baby. Then, maybe, what else might be expected? Then, maybe, because you are accustomed to hear the rhythm of speech of men who talk in practiced ways at a calm pitch, never causing alarm, you can rise among them and quietly use those words that stir the pots of financial lore and pick the bones of war and commerce, can speak of laws and policy that could move armies, cities, mountains. But how did you know, then – without rough days at school among common men – what the people might require? How roads might change the destiny of those who live among the mountains, how schooling for modern times might let impoverished children awaken to a hopeful day? Perhaps it was something you read, or heard from others’ talk, because you could not have had it in your experience, never put your hands upon it, you born of ruffles and well-laid dinners, where a granny wiped the grease from your pink cheeks, and you never felt the bite of cruel hunger. Because we are such simple creatures of habit and memory, how did you imagine the choking dust that comes of mining rock deep under the hills, the dust that enters a man’s lungs and never leaves, that smothers his very soul? Then you rose and spoke about what must be done to protect this working man, this stranger, this somehow brother. How was there sorrow in your words when you told of the black men buried quietly away in a single grave, with no memorial to their labor, their sacrifice, their lives but cornstalks brown and waving, with no apology, no justice? In this college of well-read men, most born like you in privilege, you held up the lamp of the working man and cast a light on what drives all human aspiration – hunger, work, responsibility, knowledge, justice. The man and woman by the wayside of the road were your concern, you said. But how did you know them? When were you ever there, except passing by in the parade? I think of these things you might have learned – the man who gave five talents to his servant, who then went to the marketplace and traded and made five more for his master. From those to whom much is given, much is expected. So I can understand why, in the college of well-fed men who discuss commerce and law, you might have raised the cause of the working man. But unless there was some deep bond, a resonance outside the range of hearing, I simply don’t know how you understood, when you heard it, the cry of men who bore the brunt of hungry children, no jobs, no hope, and who asked for a new deal. Hugh S. (Stan) Cavendish Biography  Stan Cavendish is a West Virginia native, retired telecommunications industry executive and volunteer leader in programs centered on education, cultural affairs and the environment. He is currently vice chair of the Cedar Lakes Foundation, treasurer of the WV Humanities Council and a master naturalist volunteer, primarily in Canaan Valley, where he and wife Carolyn maintain a second home. Cavendish was raised in Ripley and Beckley, WV; obtained a B.A. degree in English from West Virginia University; worked as a teacher and then weekly newspaper editor, before beginning work at C&P Telephone Company in 1976. He completed a 30+-year telephone career with a five-year term as president of Verizon West Virginia. While in positions focused on education and economic development, he led a successful effort (World School) to bring high-speed internet to all the public schools in the state and another (Office of the Future) to bring more than 20,000 teleservices jobs to West Virginia. He also directed Verizon’s support of the Humanities Council’s WV Encyclopedia project and eWV, the on-line version of the encyclopedia. At Verizon, Cavendish oversaw millions of dollars in focused charitable contributions, including many in support of public education, teacher training and higher education programs, and others in furtherance of enhanced 911 capability statewide. He is past chairman of the State Workforce Investment board and the WVU College of Education Visiting Committee; served on the State Community College Board, WV Roundtable, and Discover the Real WV Foundation, among others. He was honored as an outstanding Almnus of the WVU College of Arts and Sciences. Stan and his wife Carolyn, a well-known watercolorist, live principally in Charleston. They have two children and a granddaughter. The staff of the Byrd Center and its Board of Directors note with sadness the recent passing of Lex Miller, a generous donor to the Center and an active participant, with his wife Pam, in the programs and activities of the Center. We send our heartfelt condolences to Pam and the entire Miller family and to their many friends.

Lex was a model citizen, fully engaged in the life of the Shepherdstown community and the broad cultural and social aspects of this university town. His quiet manner could not hide the strong intellect, wisdom, and dedication to public service that he brought to his volunteer work with many organizations. The Millers moved to Shepherdstown in 2004, just two years after the Byrd Center opened its doors, and we were so fortunate to have Lex and Pam among our friends and supporters. Ray Smock, Interim Director

By Richard Jones

Byrd Center Student Intern

Click the maximize button (lower right corner) to view this digital timeline full-screen.

Senator Robert C. Byrd made his issues of the campaign financing system in the United States and its reform part of his agenda for the 100th Congress. In 1988, Byrd and Oklahoma Senator David Boren introduced campaign financing reform legislation. The bill set voluntary spending limits for Senate candidates in general elections in all states. The bill was met with opposition from the Senate Republican Party who led a filibuster against the legislation, arguing that the proposal favored Democrats and would restrict American citizens from participating in elections, with Senator Mitch McConnell arguing that Congress would never agree on the extent of these limitations to campaign contributions. Despite a Democratic majority in the Senate, the move for a cloture vote to end the filibuster failed seven times, though Byrd threatened to keep the Senate in continuous session until the legislation was resolved. Republican senators subsequently scattered and Byrd moved to have the Senate sergeant-at-arms gather the absentee senators to participate in a record eighth cloture vote which also failed [1]. Byrd withdrew the bill after this but made clear his intention to call up the legislation in the future.

|

Welcome to the Byrd Center Blog! We share content here including research from our archival collections, articles from our director, and information on upcoming events.

Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed