|

By Richard Jones, Byrd Center Student Intern

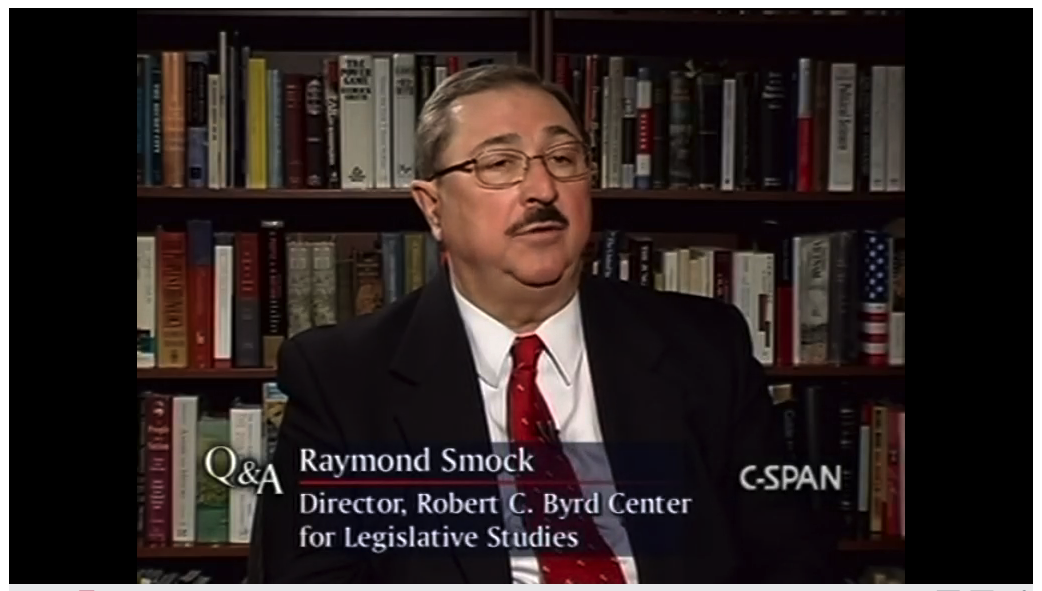

By Ray Smock The reason I am coming out of retirement to be the Center’s Interim Director is because the current director, Jay Wyatt has taken an excellent position at the Center for Legislative Archives at the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, DC. This is a great opportunity for him. I am pleased for Jay to be able to work in the part of the National Archives that oversees all the committee records of Congress going back to 1789. The volume of those records rivals those in all the Presidential Libraries. There is another reason I am coming back. I love the work. In November 2009, Brian Lamb came to the Byrd Center and conducted an interview with me for C-SPAN’s “Q&A” program. We talked about the Byrd Center and its mission, about Senator Byrd, who had just become the longest serving person in the history of the U. S. Congress, and Brian worked in a book interview about my biography of Booker T. Washington, published that year. At the end of the interview Brian asked me how long I would keep doing the work. Without hesitation I said, “I will do this as long as I can because I love what I am doing.” I stayed at the Byrd Center another nine years after that interview, retiring at age 77 in 2018. I left the Center in the capable hands of Jay Wyatt and Jody Brumage. I remained a member of the board of directors of the Congressional Education Foundation that oversees the work of the Center. I recruited Jay in 2013 to come to the Byrd Center as Director of Programs and Research, with the probability in mind that he would be my successor, and that was the happy result in 2018. Jay’s contributions to the work of the Center have been immense, including the launch of a major touring exhibit on the career of Senator Byrd that went to twenty-two sites in West Virginia, and was featured twice in the U.S. Capitol. He served two terms as president of the Association of Centers for the Study of Congress; a national organization founded here at the Byrd Center in 2005. Jay and Jody both laid the major groundwork for the Center’s expansion into teacher training institutes and civics programs for West Virginia students. The Center’s archive, including the extensive papers of Senator Byrd, are in the capable hands of Jody Brumage, who began his career here almost ten years ago, when he became a Shepherd University student intern. He has often said that his experience working in a major research collection was one of the best experiences he had at Shepherd, and that lead to his career in archival management. Under Jody’s direction dozens of Shepherd students have experienced hands-on learning in our collections. His behind-the-scenes tours of our archive are popular because of his enthusiasm and knowledge of our collections. While working at the Byrd Center he completed a master’s degree from San Jose State University in Archives and Records Management. He has proven to be a talented and versatile part of our staff. With my return, Jody will assume even more responsibility as Director of Education and Outreach. I am coming back to the Byrd Center to provide continuity while we plan for the future. We have much work to do. The Byrd Center needs to achieve a sound financial footing if it is to survive. The Center is a non-profit educational institution on Shepherd University’s campus. We receive no funds from the State of West Virginia, and the staff members of the Byrd Center are not paid as university employees. We were able to build and operate the Center in the past from funds from several large federal grants, going back to the creation of the Center in 2002, when grants from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) provided funds for program development. In recent years, the Center has relied on smaller grants for some of its programs, and from a growing cadre of local donors who have become indispensable to the Center’s survival. It is a joy to see how the local community in and around Shepherd University has stepped up to keep the Center going. Several years ago we established a “Friends of the Byrd Center” group, under the leadership of Lisa Welch. More recently, Marianne Alexander has launched an effort to raise $200,000, of which more than $100,000 has been realized in just a few months. An anonymous donor provided a $60,000 matching grant that has encouraged larger donations. Both Lisa and Marianne, along with Sue Kemnitzer, serve on the Center’s board of directors. We are working diligently to seek grants from the federal government, from private foundations, and from supportive entities like the West Virginia Humanities Council, which has helped us with grants to conduct our teaching training institute. It would be a tragedy if the Byrd Center closed its doors and folded its tent, especially at such a crucial time in U.S. history when the nation is in a major struggle to save American democracy. Like millions of Americans, I am still in shock over what happened at the U.S. Capitol just weeks ago. A mob of American citizens engaged in an insurrection against the greatest symbol of democracy in the world. They violently invaded the Capitol to stop the peaceful transfer of power in our presidential election. Nothing like this has ever happened before. Even in the depths of the Civil War, no Americans attacked the Capitol. Yet just weeks ago Confederate flags were carried into the heart of our democracy, some used as weapons to assault members of the Capitol Police. Some of those in the riotous mob were former members of the U.S. military, who had sworn an oath to defend the Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic. Something is terribly wrong when that oath gets turned up-side-down. The rioters shouted “This is 1776” as if they were patriots just like George Washington. The Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education should be a part of a national network of institutions that promote a better understanding of Congress and the Constitution. We need all schools and all universities to take up with new urgency the need for public education about the purposes of government and the meaning of democracy. The federal government and all state governments must re-evaluate the importance of history and civics education. “Knowledge is Power,” Frances Bacon said at the end of the 16th Century. That idea was burned into the minds of the Founders of this nation who saw the importance of knowledge about government to be of vital necessity to a free people who sought to governed themselves. One of my favorite quotations of James Madison, who did so much to make our Constitution a reality, is: "Knowledge will forever govern ignorance, and a people who mean to be their own governors, must arm themselves with the power knowledge gives. A popular government without popular information or the means of acquiring it, is but a prologue to a farce or a tragedy or perhaps both." My friends, we are in the midst of both a national farce and a national tragedy of monumental proportions. Ignorance is governing knowledge. Ignorance has been spread like wildfire by lies and misinformation through social media and polarized news. Ignorance has been spread from our own White House.

For the last half century there has been a steady erosion of confidence government at all levels. This undermines civil discourse and respect for constitutional government. Voters too often send people to state legislatures and to the U.S. Congress who are elected because they proclaim government is an evil that is standing in the way of their freedoms, when the opposite is the case. Senator Byrd saw this erosion. He saw the hardening political lines that prohibited compromise. He saw how ignorance of history led to distortions about the narrative of America. Before he passed Senator Byrd had appropriated more than a half billion dollars in teacher training in history. This was a national program. Senator Byrd feared, as Madison and Jefferson feared, that a people ignorant of their own history and their own government was the greatest threat to the success of our experiment in representative government. Without public knowledge of government, it could succumb to demagogues and tyrants. In 2010, when Senator Byrd passed, his Teaching American History program died with him. That idea no longer has a champion in the United States Congress. Education at all levels has suffered from the neglect of history and civics and we are paying a dear price for it. With the help of all the Friends of the Byrd Center, I pledge to work to keep this vital part of the Shepherd University campus and this active community of citizens going strong as long as I can, until my successor is found. And it will be hard to find a strong successor unless we can demonstrate that our financial house is in order for the foreseeable future. My heartfelt thanks to the faculty and staff of Shepherd University and to the many Friends of the Byrd Center, and to our Board of Directors, for all your support and encouragement as I return, for a time, to the task I love. Byrd Center Director Dr. Jay Wyatt to take position at National Archives and Records Administration. Dr. Ray Smock, Byrd Center Director Emeritus, to return as Interim Director. The Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education announced today that Dr. Jay Wyatt will resign as Director effective February 1, 2021. Wyatt will join the staff of the National Archives and Records Administration's Center for Legislative Archives in Washington, D.C.

Wyatt joined the Byrd Center staff as Director of Programs and Research in 2013 and led the development of numerous popular public program series, exhibits, and educational initiatives. In 2018, he was named Director following the retirement of the Byrd Center’s Inaugural Director, Dr. Ray Smock. Joe Stewart the Chairman of the Byrd Center’s governing board said “while we are sorry to lose the outstanding service of Jay Wyatt at the Byrd Center, the Board is thrilled with the national recognition of his unique talents. We extend our heartiest congratulations to Jay.” The Byrd Center’s board of directors unanimously passed a resolution of distinguished service at its meeting on January 27, citing Dr. Wyatt’s many contributions to civic education and public outreach through the Center’s programs and research. The board earlier promoted Mr. Jody Brumage, the Center’s Archivist and Office Manager to the position of Director of Education and Outreach in recognition of his leadership role in the Center’s educational programs. Dr. Ray Smock, the Byrd Center’s Director Emeritus, will return as Interim Director. Smock served as the Center’s director from 2002 until his retirement in 2018. Smock was the Historian of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1983-95. Chairman Stewart extended special appreciation to Smock for “generously agreeing to resume the directorship of the Byrd Center.” The Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education is a private, nonpartisan, and nonprofit educational organization located on the campus of Shepherd University. Its mission is to advance representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens. By Jody Brumage On February 11, 1928, Captain Guenette E. Ferguson, the highest ranking Black World War I veteran from West Virginia, addressed a large crowd gathered in the small mining town of Kimball in McDowell County. The audience was assembled to dedicate a new community building for the town that was built as a memorial to African American veterans of "The Great War" and was the first such monument to Black soldiers completed anywhere in the United States. In his remarks, Captain Ferguson gave each of the four massive brick and terra cotta columns that grace the building's classical facade a label: faith, hope, charity, and service. This symbolic gesture expressed the sacrifice of veterans who not only faced the danger and difficulty of serving their nation in the Armed Forces, but did so in the face of racism and discrimination. In 1999, these attributes also came to embody the struggle of a grassroots organization from the community that sought to restore this monument which had suffered decades of neglect only to be gutted by arson. This group persevered and saved a national treasure. Shortly after the end of World War I, Black citizens in McDowell County, located in the heart of West Virginia's southern coalfields, petitioned their county government for funds to erect a community center and war memorial to the over 1,500 black men who served in the war from the county. Under the organization of the Luther Patterson Post 36 of the American Legion, Hassell T. Hicks, an architect from the city of Welch, was commissioned to design the memorial which would be a community center for Kimball. By Allison Wharton, Byrd Center Student Intern The censorship of the internet, particularly on social media, has been a topic of scrutiny and political debate this year. While social media allows for easier spread of ideas and can be used by businesses and professionals for marketing, it is widely regarded as a form of entertainment rather than a medium with any major educational value.[1] The popularity of social media in the 21st century has surpassed traditional forms of media entertainment such as television, but the debate over censorship and the purpose of social media is a continuation of long-standing discussions over the constitutionality of entertainment regulation, which has been addressed by all three branches of government over the past fifty years.[2]

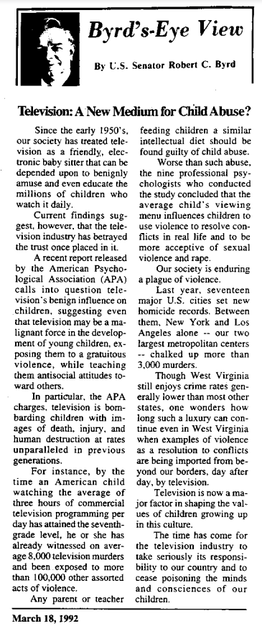

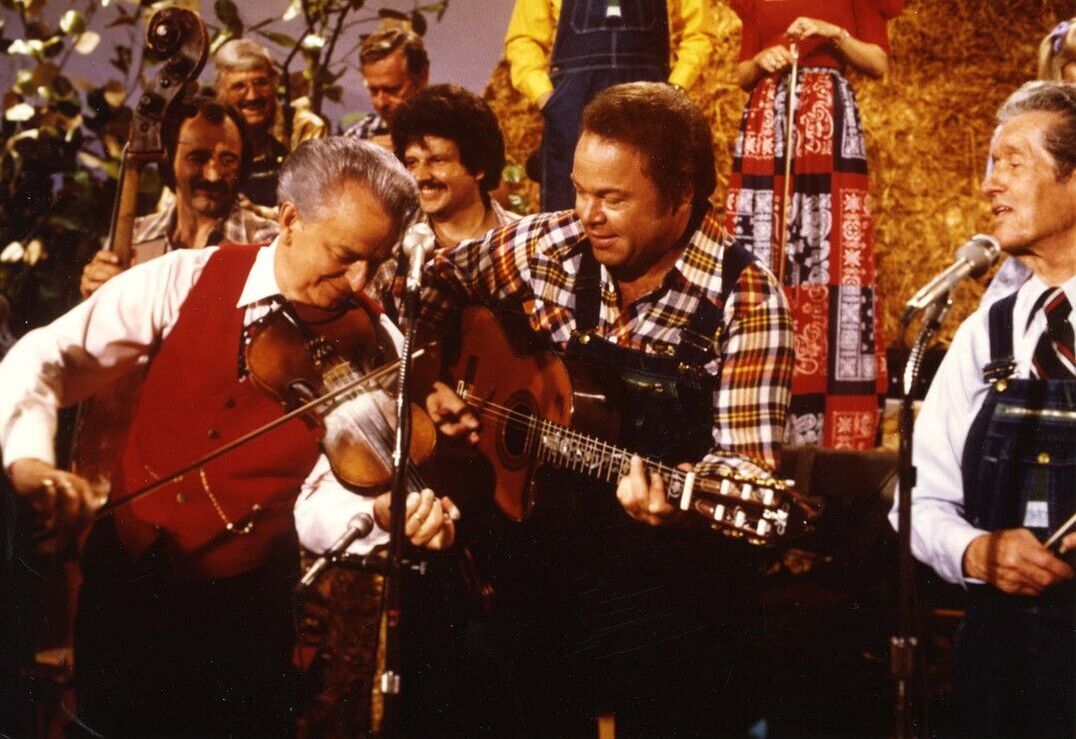

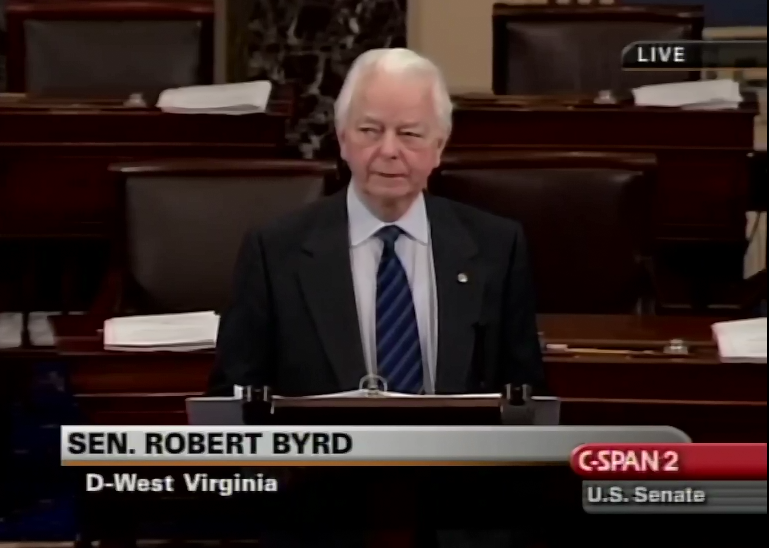

Byrd also wrote about a decrease in crime rates nationally and in West Virginia, and believed that there was an increase in juvenile crime rates that was the product of culture being uncensored and marketed to children. With violence and drug use becoming more common among minors in America, Byrd maintained his stance against television, film, music, and video games depicting crime being marketed to children, arguing for regulations and an updated system of ratings for entertainment deemed inappropriate for young people. Though Senator Byrd was quite vocal about his problems with entertainment media, he also recognized the potential benefits. He believed that television and music would be better used for educational purposes than entertainment. Byrd grew up learning how to play the fiddle, recording an album and frequently playing at public appearances throughout his adult life. While arguing for regulation of the music industry, Byrd did recognize its merit. He also appeared on the show “Hee Haw,” despite his seemingly outspoken opposition to television and argued that a “Family Hour” program was necessary for the entertainment industry because it would provide appropriate forms of entertainment that could also be educational. Senator Byrd was initially lukewarm to the idea of televising floor proceedings of the U.S. Senate when C-SPAN was created in 1979. However, he came to realize the democratizing value that television coverage of the Congress could build and he ultimately became an ardent supporter of allowing cameras into the Senate Chamber in 1986. Byrd’s belief in the regulation of entertainment media was due to his hope for the youth of the country to be better educated rather than to be exposed to themes he cited as the cause for increase in juvenile crime. According to the Federal Communications Commission, material considered “indecent” is protected under the First Amendment and cannot be completely censored.[3] Various members of Congress have spoken both for and against censorship of entertainment and the Supreme Court has a long history of cases on obscenity charges and freedom of speech.[4] Byrd’s reputation as a strict constitutionalist despite rulings to protect entertainment media from censorship reflects the complexity of regulation of the entertainment industry that is still happening today. Social media serves as a form of short-term entertainment, while the shift toward more fact-based and educational usage has the potential to have a larger impact.[5] However, lack of censorship makes the validity of claims more difficult to confirm and potentially allows for the posting of more obscenities, while over-censorship or censorship of free speech would be deemed unconstitutional. The same arguments on social media regulation existed long before in discussion of the censoring of television and music. The debate on social media censorship, fact checking, and algorithmic issues are an extension of larger debates about entertainment that stretch back to the mid-20th century and continue into contemporary discourse. Sources:

[1] Stuart Cunningham and David Craig, Social Media Entertainment: The New Intersection of Hollywood and Silicon Valley, (New York: NYU Press, 2019), 8-11. [2] “A Brief History of Film Censorship,” National Coalition Against Censorship, Accessed June 20, 2020, https://ncac.org/resource/a-brief-history-of-film-censorship. [3] “Consumer Guides: Broadcast, Cable, and Satellite,” Federal Communications Commission, Last modified May 18, 2020, https://www.fcc.gov/general/broadcast-cable-and-satellite-guides. [4] “Freedom of Expression in the Arts and Entertainment,” American Civil Liberties Union, February 27, 2002, https://www.aclu.org/other/freedom-expression-arts-and-entertainment. [5] Brian Patrick Green, “What is the Main Purpose of Social Media: Entertainment or Education?” Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University (blog), December 16, 2019, https://www.scu.edu/ethics-spotlight/social-media-and-democracy/what-is-the-main-purpose-of-social-media-entertainment-or-education/ By Patrick Fuller, Byrd Center Student Intern From the end of World War II until the early 1970s, a period of great economic expansion swept across the United States. The American middle class experienced substantial growth and found themselves with extra spending money. With the advent of many time-saving home appliances, many Americans also found themselves with extra time for recreation. Naturally, the excess of time and money led to the desire for travel.

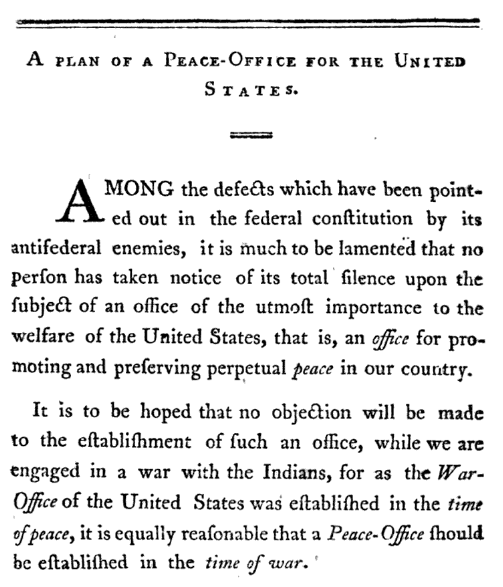

This year, the Byrd Center has worked with over 125 educators in our first virtual Teacher Institute, exploring how Congress and the foundations of our representative democracy have been tested in critical moments of American history. One of the workshops these teachers have participated in is a deep dive into the way our country has historically decided to go to war and how those precedents were challenged in the wake of the September 11th terrorist attacks. In this workshop, we look back to the crucial debates and votes that took place on the House and Senate floors that brought the United States into one of its longest and most complicated military engagements. Senator Robert C. Byrd garnered national attention for his outspoken opposition to the Iraq War in late-2002 and early-2003. He even published a book of his speeches and commentary on the war entitled Losing America in 2004. The Byrd Center’s archives preserve thousands of letters that poured into the Senator’s office in response to his statements against the war, revealing a deeply divided nation. These documents along with the Senator’s own words reveal how the War on Terror in many ways shifted the power of war within the government and set new precedents for foreign policy in the United States. Over a year before Senator Byrd leveled his condemnation of the Senate “standing passively mute” amid the ramping up of the war in Iraq, another elected representative took a courageous and bold step to raise a warning about the dangerous precedents that were being set with the War on Terror. Just three days after the horrific terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, as people across the United States continued to mourn and grapple with shock and a sense of paranoia, a historic act of dissent occurred on the floor of the House of Representatives. Shortly before Congress voted overwhelming in support of the Authorization for Use of Military Force against global terrorism, the lone voice of California Congresswoman Barbara Lee urged caution. “September 11th changed the world. Our deepest fears now haunt us. Yet, I am convinced that military action will not prevent further acts of international terrorism against the United States,” Congresswoman Lee stated, “some of us must urge the use of restraint.” Despite the vitriolic response that poured into her office in the days and weeks after her speech, Congresswoman Lee remained a resolute opponent to the course of action the United States decided to take in responding to the threat of terrorism. Her bravery laid the foundation on which 133 members of the House and 23 Senators, including Senator Byrd, stood just eleven months later when voting against the Iraq War Resolution. In his speeches and writings, Senator Byrd reflected on his actions in relation to another military conflict that challenged the execution of war powers in the United States. In interviews, Senator Byrd was frequently asked about his support for the Vietnam War, to which he responded that while his actions seemed correct at the time, in hindsight, he, and the rest of the country, was wrong. Congress itself made this realization before the Vietnam War ended when it passed the contentious War Powers Resolutions of 1973, overriding the veto of President Richard Nixon to reassert Congressional oversight and authority in matters of conducting war.

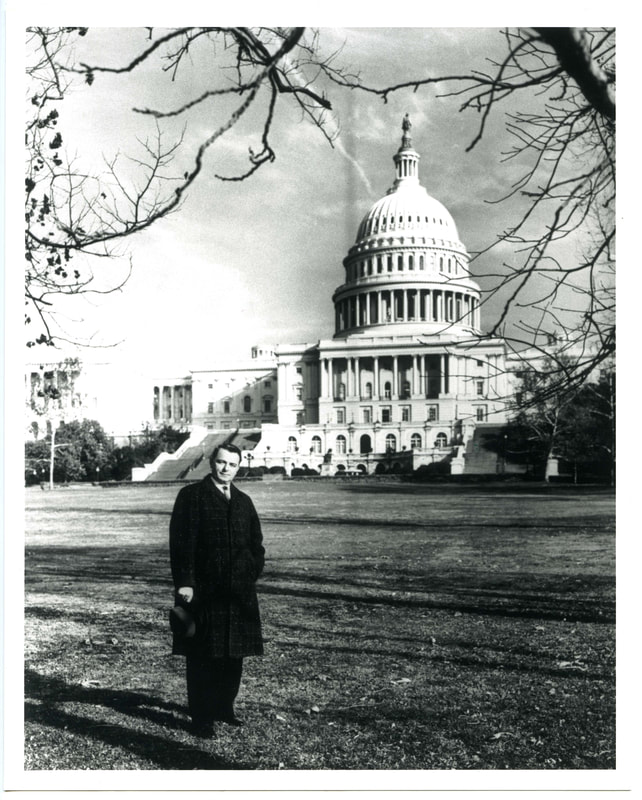

Our Teacher Institute workshop on this subject relies on the speeches, constituent letters, press interviews, and legislation that have determined our country's response to international crises. Comparing the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force with the 1941 Declaration of War passed by the Congress against Japan in retaliation for Pearl Harbor exposes the broad war powers granted to the president in 2001. Learning about the War Powers Resolution of 1973 helps us understand the push and pull of separation of powers and how this has played out in our nation's history. And examining the words of Congresswoman Lee and Senator Byrd, we see the need for deliberation and critical thinking to avoid rash decisions that do not take into account the potential consequences. Almost twenty years later, the prescience of Congresswoman Lee’s warning continues to bare on our discourse around the War on Terror. Her opposition to the notion of a war without a stated end goal, with no consideration of long-term foreign policy or economic implications, all subject to the decision of the executive with little oversight from the legislative branch, was the same mantel used by Senator Byrd in 2002 as he opposed going to war in Iraq. Indeed, a growing number of Americans now view these decisions with increasing regret as we grapple with the full impact of our actions and the lives of soldiers and civilians lost. In September 2008, Senator Robert C. Byrd was presented with an award from the National Council for History Education in recognition of his longstanding commitment to the improvement of educational resources and opportunities for studying American history. The award was presented by Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David McCullough, who joined Senator Byrd in the effort to establish federal funding for history education eight years earlier in 2000. By Ray Smock It was ten years ago this month that Senator Robert C. Byrd died on June 28, 2010. He was given the rare honor of lying in repose in the Chamber of the U. S. Senate. His funeral service in Charleston, West Virginia, was attended by tens of thousands of people, white and black, many of whom, the evening before, had walked along Kanawha Boulevard behind the senator’s horse-drawn casket on the way to the gold-domed Capitol. The world, today, always changing, seems so distant from 2010, when Barack Obama was the last of eleven U.S. presidents that knew and worked with Senator Byrd. Byrd Center Director Ray Smock with Senator Robert C. Byrd at the center in 2005.

|

Welcome to the Byrd Center Blog! We share content here including research from our archival collections, articles from our director, and information on upcoming events.

Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

Our Mission: |

The Byrd Center advances representative democracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States Congress and the Constitution through programs and research that engage citizens.

|

Copyright © Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed